For many native Washingtonians, the opioid epidemic didn’t start with addictive prescription medications from doctors. It began with chronic heroin use.

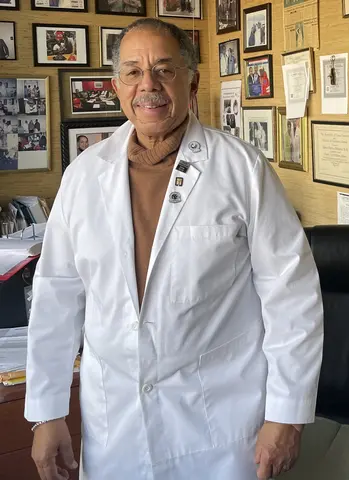

Dr. Edwin Chapman, a physician and addiction medicine specialist in Washington, D.C, provides medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder, and works closely with D.C. residents who have battled heroin addiction for years. For most of his patients, their addiction did not start with medicine from the doctor, and instead, is a result of the heroin and crack-cocaine epidemics that have been prevalent in this area since the Vietnam era.

Most of Chapman’s patients have experienced addiction for decades and have personally seen the impact that fentanyl has had on their community. One of Chapman's patients shared, “I’ve lost a lot of friends. I started losing two at a time—[they're] together getting high. The drugs they got—it's fentanyl.”

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that is 50 times more potent than heroin. It appeared in the D.C. area starting in 2013 and began to contaminate the heroin supplied to the region. With the rise in fentanyl, the District began to see a rise in fatal overdoses peaking at 411 deaths due to opioid drug overdose in 2020.

In an effort to halt the rising death toll and reduce opioid use and misuse, the D.C. government launched the “LIVE.LONG.DC.” Strategic Plan in 2018 to serve as a blueprint for combating the opioid crisis. Although the plan has increased the availability of harm reduction resources throughout the city, Chapman believes “our response has been much slower than the street response.” He is worried about the growing national culture that is dismissing science, especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, and he fears that people will not accept new harm reduction strategies even if there is science to support it.

One of these potential strategies is a supervised injection site. Supervised injection sites, often referred to as safe consumption sites or harm reduction centers, are spaces for a person to use their drugs in a hygienic environment that is staffed with trained personnel who can administer naloxone in the case of an overdose. The distribution of new syringes at these sites prevents the spread of infectious diseases, including HIV and Hepatitis C. Overall, they aim to create a safe and stigma-free environment with a streamlined connection to physical and mental health, and social services that can guide a person towards recovery when they are ready.

Rhode Island was the first to approve legislation for pilot programming to launch these centers, and New York City recently authorized the opening of two such sites in Manhattan.

For Washington, D.C., the “LIVE.LONG.DC” Strategic Plan budgeted over $6 million to “support the awareness and availability of, and access to, harm reduction services,” including $100,000 of funding for the consideration of supervised injection sites. In December 2019, a recommendation outlining a viable option to consider implementing a supervised injection site was delivered to the Director of D.C. Department of Behavioral Health, D.C. Health, and Department of Human Services, but no further action was taken.

A member of this team was Cyndee Clay, the executive director of HIPS, a community-based harm reduction organization that promotes the health, rights, and dignity of those engaging in sex work, sex trade, and/or drug use. According to Clay, “HIPS stands absolutely ready to partner with any private funders who would be interested in supporting such an effort.” However, she adds, “[Given] D.C.’s specific situation of congressional oversight… it would be nearly impossible for public funding of such a site.”

The lack of statehood in Washington, D.C. presents as a barrier to expanding harm reduction to include supervised injection sites because both the federal and local portions of the District of Columbia’s fiscal budget require Congressional approval.

In 2019, the opioid death rate in D.C. ranked fourth in the country with fatal opioid overdoses occurring in 33.7 per 100,000 people, compared to a death rate of 15.5 per 100,000 people in the United States. This is especially devastating for the communities of color that are disproportionately affected by the opioid epidemic in Washington, D.C. According to Kaiser Family Foundation, in 2019, 90 percent of fatal opioid overdoses in Washington, D.C. involved Black, non-Hispanic people, higher than any state in the country. In neighboring Maryland, 39 percent of opioid-related deaths were among Black, non-Hispanic people, ranking second highest in the country.

In this region, fatal overdoses are occurring at disproportionately higher rates within the Black community than anywhere else in the United States. Chapman explains that “initially it was suggested that this was driven by community and stress, and now, people are talking about structural racism as the underlying cause. If you look at the history of this country… starting with slavery, each era had its own defined structure.”

For Washington, D.C., a supervised injection site may be an approach not only for preventing fatal opioid overdoses, but also building a more equitable healthcare environment for people who use drugs. However, even as national momentum and advocacy for supervised injection sites continue to grow, and data surrounding their community impact becomes more comprehensive, these sites will first need to overcome the ongoing legal, political, and social barriers that so strongly govern our public health.