On a sunny afternoon this past summer, several fishing boats milled about in Cordova’s harbor. Rain clouds lingered over the Chugach Mountains, which surround the small Alaskan fishing community. Seagulls called overhead, and the salty smell of fresh salmon was sharp in the air.

The harbor was quieter than usual. Shiny metal hand-washing stations stood at the ready. As a boat approached, crew members wearing face masks prepared to dock. The boat flew a solid yellow flag—no one on the vessel was sick with COVID-19. A black-and-yellow-checkered flag would mean the boat is in quarantine.

From fears about visitors to the state for the fishing season bringing the virus into Alaska’s rural communities, to the logistics of quarantining on boats, fishing looked different in summer 2020.

These new challenges landed particularly hard on a growing subset of fishermen: women.

Although the industry is historically male-dominated, the number of women working in Alaska’s seafood industry is increasing, women fishermen say. Women are not only fishermen, but also work in processing, direct marketing, managerial jobs, and sales positions on the shore.

The International Organisation for Women in the Seafood Industry (WSI) predicts the COVID-19 pandemic will impact women more than men and intensify gender inequalities already present in the industry. Women face barriers such as gender discrimination and carry responsibilities that men typically do not, such as balancing fishing and caring for children.

“If the seafood industry was a country, it would be one of the most unequal on Earth,” Marie Christine Monfort, executive director of WSI, writes in an email.

However, addressing gender inequality in the fishing industry is difficult. Data on the number of women working in the fishing industry in Alaska, and most countries worldwide, is lacking. This means the roles women play in fisheries are not well understood.

The impacts of COVID-19 will likely exacerbate the challenges women fishermen face. Researchers and international organizations have studied gender inequality in the industry and what it means to be a woman on the water prior to the pandemic. Now, understanding the experience of this unrecognized community in the fishing industry is more important than ever.

Fisherman Kinsey Justa and her partner were fishing in Cordova, Alaska, when COVID-19 hit.

Cordova’s fishery is generally the first salmon fishery to open in Alaska every year in May. Other Alaskan fishing communities were watching how Cordova would handle pandemic precautions. Fishermen wore masks on their boats and in the harbor. Captains registered crew member information with the city of Cordova. Fishermen quarantined on boats and were tested. If anyone on boats had symptoms, they had to fly quarantine flags.

“Cordova was very compliant,” says Justa. “I think we had at most maybe seven cases at one time. It’s a small community and is closely knit.”

Alaskan fishermen are essential workers and food producers, as well as small-business owners. At the start of the pandemic, fishermen and seafood companies sold more retail frozen seafood in March and April 2020 than ever before. As COVID-19 panic spread across the country, Americans hoarded toilet paper and filled their freezers in preparation for whatever was to come.

This increase in revenue quickly reversed when restaurants closed. Fishermen who sell fish wholesale to restaurants lost their markets and had to pivot to direct marketers. This situation was especially challenging for small scale fishing businesses. Fishermen couldn’t sell their products from the last fishing season as planned. Many fishermen were also unsuccessful selling their fish on the fresh market.

Despite issues selling products, fishing itself was largely unchanged. The nature of fishing allows for fishermen to remain socially distanced. Justa explains that COVID-19 did not have a significant impact on her fishing, especially when COVID-19 precautions can be easily followed when out on a fishing boat.

“It really felt like an escape from the real world. We were pretty fortunate to be socially isolated on a boat in Alaska,” Justa says.

Cordova fisherman Kinsey Justa working aboard a fishing vessel. Image courtesy of Kinsey Justa. United States, 2020.

Despite growing up in the mountains of Colorado, Justa has always had an interest in seafood.

“I think it's a super interesting resource,” she says. “There's no other food in the world that's wild that we harvest on the scale that we harvest seafood. I like it because it's visceral. It's a really direct contact with something that's super important, which is food.”

Justa started working in the seafood industry six years ago, doing marketing for a regional seafood development association in Cordova. She then transitioned into sales for a small processing facility. For the past two years, she has been harvesting salmon, crab, and shrimp aboard a fishing boat with her partner.

Justa also likes that fishing allows her to have a flexible lifestyle. She fishes in Cordova in the summers seasonally. For most of the year, she is doing research as a graduate student at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. Fishing allows her to make all of her income during the summer during the fishing season, and then she can focus on schoolwork for the rest of the year.

Women often play an adaptive role entering and exiting fisheries in response to changing conditions in their lives, such as being a student or becoming a parent. Many women juggle the responsibilities of child care and fish in areas using certain fishing methods that allow them to watch children simultaneously, explains Marysia Szymkowiak, a social scientist at the NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center who studies fisheries.

Salmon fishing takes place during the summer fishing season. In the summer, there are safer weather conditions so kids can be brought along on the boat. Women dominate set net salmon fisheries in Bristol Bay, Alaska. A skiff is used to set out a net to catch fish from the shore, where children can stay close by.

“It's, in part, a little bit cyclical,” explains Szymkowiak on why women participate in certain areas of fishing. “Moms are able to take their kids to participate in these fisheries. And then those are the fisheries that their daughters participate in.”

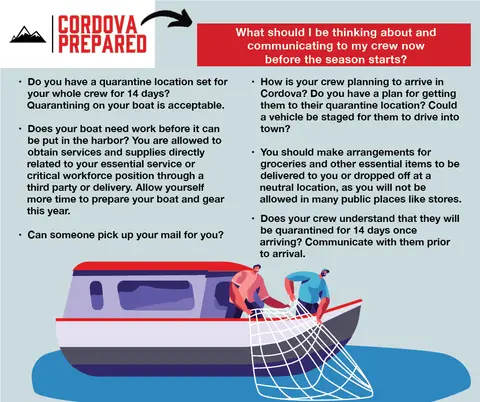

A graphic that is part of a series explaining COVID-19 protocol for Cordova fishermen. Designed by K. Justa for the City of Cordova.

Other women act as financial buffers for their families by working jobs on the shore to support fishing operations conducted by men out on the water. Wives of fishermen play essential roles running direct-marketing businesses, shipping fish, and getting in contact with buyers to sell fish directly. Many younger women fish part time and are dating or married to someone in the fishery.

“It's funny, whenever people ask me, ‘How do you feel being a part of a male-dominated industry?’and it doesn't feel like that at all. Just because you're not seeing as many women on the boats doesn't mean that it's male-dominated,” says Justa. “The industry is so much bigger than just catching the fish.”

For Bristol Bay fishermen, the history of another pandemic prompted difficult decisions about whether to participate in the summer 2020 fishing season.

Around a hundred years ago, the 1918 flu pandemic devastated Bristol Bay. Fishermen coming from out of state for the fishing season brought the virus with them, infecting local communities. That history made a number of fishermen think twice before coming to Bristol Bay in summer 2020 as COVID-19 cases rose across the United States.

Fisherman Elma Burnham made the challenging decision not to come to Bristol Bay. She feared bringing COVID-19 to the community, especially to Indigenous communities. In April 2020, tribal leadership asked Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy to shut down the Bristol Bay fishery due to fears of a COVID-19 outbreak. The fishery remained open.

“The virus was becoming so real, and I was starting to worry about going to Bristol Bay,” says Burnham. “There were a lot of people who were concerned about Bristol Bay for various reasons, but primarily because, ‘What if we bring this virus to a place that doesn't have it?’”

Burnham instead worked on an oyster farm on Fishers Island, New York, run by her uncle. She also spent time reading and learning about tribal sovereignty and history in Alaska.

“I want to make sure that the local community of Bristol Bay continues to want to welcome fishermen from out of state,” she says. “White settlers from the lower 48 that are going up there should learn more and be able to honor tribal leadership better in our fishery.”

The gender discrimination women face in fisheries is both unique to fishing and a metaphor for the experiences of women everywhere. Strangers often assume women are the daughter of a fisherman or married to someone in the fishing industry. In reality, many women fish independently and own their own boats.

“If in school a professor says something sexist, there’s going to be other women in the class who recognize that immediately,” explains Burnham.

“But when you’re the only woman on the boat or the only woman who’s witnessed that comment in the boat yard, it’s lonely. It’s easy to gaslight yourself out of it and think, ‘It's not a big deal, I’m just here to be one of the guys.’”

Harassment and sexual assault on fishing boats is an ongoing issue in fisheries. Fishing can be extremely dangerous for women who fish on boats that leave port for multiple months.

The expectations of women are also different than men and reflect traditional gender roles. Women have complained of being hired as a crew member expecting to learn how to fish, only to end up cooking or taking care of children, says Burnham.

Some gender discrimination in fishing can be very nuanced. “Women are expected to make the weather call and say when it’s too rough to go out fishing. That responsibility shouldn’t be exclusively up to me because I’m the female, mothering, nurturing role. The whole crew should be responsible for keeping each other safe.”

Burnham is also the founder of Strength of the Tides, a community organization with the goal of supporting, celebrating, and empowering womxn, trans, and genderqueer people who work on the water.

The Strength of the Tides Instagram page highlights fishermen and their stories. A pledge on the website asks members of the seafood industry to commit to making the industry a safe place free of sexual assault, discrimination, and harassment. There are over 500 signatures to date. Burnham has future goals of providing more education events through Strength of the Tides to help women who are just starting out to find their place in the fishing industry.

The International Organisation for Women in the Seafood Industry (WSI) is a nonprofit founded in December 2016 by seafood professionals and gender experts to increase awareness of gender inequality in the fishing industry. The organization strives to work with public and private seafood stakeholders to adopt policies and practices to fight gender discrimination in the industry, according to its website.

WSI reports that, globally, one in two seafood workers is a woman. However, this rough statistic was first compiled by the World Bank and may have no scientific precision, explains Monfort in an email. Many social scientists have demonstrated the important contributions of women in fisheries. However, accurate statistics on women in the fishing industry are still largely nonexistent both in Alaska and around the world.

“Public authorities pretext the lack of statistical information to justify their absence of actions,” says Monfort. “More data would help to better understand the economic and social organization [of the seafood industry] by gender and help design more precise and efficient actions.”

The official statistics on Alaska fisheries participation are collected from fishing permits. Gender information is not included on these permits. This means data on fisheries does not consider the different positions women occupy in the fishing industry. When this data is used to create policy, women are left behind.

“You’re going to miss a big part of the picture,” Szymkowiak says. “Your predictive models in terms of trying to figure out how people are going to respond are not necessarily going to be correct because you’re assuming men and women are the same.”

In her research, Szymkowiak used software to assign the probability of a gender to 30 years of data from fishing permits in Alaska. The software assigns gender to data from the permits such as names and other information. This method had over 90% accuracy and can help fill in the gaps regarding the number of women and the positions they occupy in fisheries.

The nature of fishing allows fishermen to easily remain socially distanced. Image by Kinsey Justa. United States, 2020.

There are multiple ways the pandemic could impact women fishermen. For now, it is too early to determine long-term trends.

“I want to look at the 2020 harvest data as soon as I think it’s safe and represents the season [and] just look at initial numbers,” Szymkowiak says. “I’m interested in looking at the data and thinking about the long-term ramifications. I’d hate to see women lose out because of the pandemic.”

Since COVID-19 protocol encourages people not to interact with those outside their household, women might come aboard fishing boats in the place of paid crew members. Other drivers like suddenly having children at home more due to remote learning could cause women to participate less in the fishery.

Fishermen need experience to be able to build up capital and gain their own harvesting privileges. If women stop participating in fisheries due to the pandemic, it could be difficult for them to return to fishing.

Will the impact of COVID-19 cause women to participate less in the fishing industry in the near future?

“That’s the million-dollar question,” says Szymkowiak.