In a neighborhood that quickly boarded up and felt abandoned by the end of March, it was hard not to wonder what would happen to the Mission District’s large immigrant population. Nannies, construction workers, and small business operators were either unemployed or venturing out to grocery stores, construction sites, or gig economy jobs, praying that they did not bring the virus home.

The Mission District’s social service agencies went into action, calling their clients to check-in, but their physical storefronts shuttered. One morning I watched a couple knocking on the door of one of the agencies. I explained that the social workers had to take calls from home, that they should use the number posted prominently on the front door. But we want to see someone, one of them said. I explained again why that was impossible. When I left, they were still standing outside, peering in, waiting.

That image stayed with me. I wondered what would happen to so many people in need. And then walking one day on 20th Street, I followed a line of immigrants with shopping carts to a truck on Alabama Street. Boxes of food were being loaded off to hand out to the people in line. I asked who was in charge. The Latino Task Force, I was told. In the weeks that followed, that was a name I would run into everywhere – not in constant press releases, as they had no time for that – but in the street. Working.

I continued to see its workers at the Alabama Food Hub where the line grew week by week. I ran into its volunteers going door to door in mid-April to talk to Mission residents about participating in a COVID-testing study with UCSF. I met them later at the testing sites. In mid-June, a wide-open door at 701 Alabama St. led to a large airy room where experts in housing, medicine, and other resources met clients “cara a cara” to fill out applications for unemployment claims, housing, food stamps, and other benefits. And by the second week in July, the Latino Task Force had convinced the city to add a mobile testing site at the Resource Hub – a testing site that opened Thursday to some 200 people waiting to be tested.

The city’s Latinxs, it turned out, had not been abandoned. Instead, at a time when gentrification seemed to blunt the power of Latino activists, the Latino Task Force is demonstrating how years of training, deep roots, and savvy leadership can muster a force that has been more visible than any city agency. It is a child of the pandemic, but the task force is led by people who have been activists since the 1970s. It’s clear now that all of their life experience — even their early years as low-riders and dirt bike enthusiasts, as parents raising families in the Mission and especially as political hellraisers — prepared them for precisely this moment in time. And they’ve found they are up to it, to a degree that has surprised even them.

“It’s hard to explain how this happened so quickly,” said Valerie Tulier-Laiwa, who now works with the Public Utilities Commission, and is one of six members — one man and five women – on the task force’s executive committee. “There is a Mission way of doing things,” she says and pauses, trying to explain what that means before she finally concludes, “We get things done.”

Tulier-Laiwa and her colleagues ought to know about the Mission way. Over the past four decades and change, most have alighted at all the signposts on that route: San Francisco State University, the Mission mural programs for youth in the 1980s, RAP (an alternative high school of the 1990s), Loco Bloco, Carnaval, the Beacon After School program, Mission Girls, and the Mission Peace Collaborative. And while some of those efforts are ancient history, the time spent at each formed values and friendships that endure. The elders have perpetuated their legacy by mentoring a younger generation, some of whom have joined the task force today. What’s more, many of these longtime Latinx activists now hold government posts. They are no longer on the outside looking in, but making a difference from the inside.

An email grows to a group text and the Latino Task Force emerges

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly how the Latino Task Force first emerged in March, but several members say it began with an early email Veronica Garcia, a policy analyst at the Human Rights Commission, sent Tulier-Laiwa, her one-time mentor. Garcia, 35, was seeing the crisis unfold firsthand as her father, a dishwasher, got laid off. That email quickly morphed into a text message chain and conversation with others: Roberto Hernandez, known unofficially as the Mayor of the Mission, who is generally working on Carnaval at this time of the year; Tracy Gallardo, now a legislative aide to District 10 Supervisor Shamann Walton; and Gloria Romero, who now works at Instituto Familiar de la Raza.

Except for Garcia, they were all elders with years of experience in community-based organizations and city government. Seeking a voice on education, they reached out to Gabriela López, the vice president of the school board — and, at 30, less than half the age of some of the founding board members. López had never worked in a community-based organization (CBO), an experience that Tulier-Laiwa and Gallardo view as foundational. But Gallardo had worked on López’s campaign for the school board and had a hunch she would be effective. “She didn’t come from a Mission CBO,” says Gallardo, “but she has been kicking ass and doing super amazing incredible work.”

Early on, the group found ready backing from Garcia’s boss Sheryl Davis, the executive director of the Human Rights Commission, a Black leader who has a strong belief in grass-roots enterprises. You need staffing? Check. Fliers? Check. Relief from your regular duties? Let me call your boss. “She leveraged her position to help us,” said Garcia. And Davis, who is delighted with the results, plans to continue. She has her eye on the city’s August budget process and has already asked the mayor to think about funding from-the-ground-up community partnerships. She is preparing to go into the budget negotiations armed with input from multiple town halls on how the city should spend the money it plans to re-allocate from the SFPD.

Walton, who along with District 9 Supervisor Hillary Ronen has worked closely with the task force noted another reason for the task force’s early and continued visibility. “They came together to respond without relying on philanthropy or waiting for the government to come in,” Walton said. In other words, they took the lead.

And many followed. The task force has ultimately spun off 13 committees and various subcommittees, many of them staffed with people who work for community-based organizations. It’s a bench deep with talent ready to jump in and play, but the executive board is picky. “We don’t have time for people to be on a committee so they can put it on their resume,” said Tulier-Laiwa, a one-time lowrider with multiple degrees who others talk about with a mix of respect and just a little bit of fear. “We ask, ‘what can you bring in?’ We’re very action-oriented.”

Added Romero, who once rode a dirt bike, and also accumulated degrees and experience: “We’re Latina women — community workers. We are essential. We have been, throughout history. We get things done.”

That is clear during the hour-long Monday morning calls the executive committee has with its committees, more than 30 community-based organizations and a cadre of local elected officials. What could easily have been a case of too many well-meaning people running in too many directions, is instead a well-oiled machine under Tulier-Laiwa’s control. Each speaker gets one minute.

“Do not mess with Valeria and talk over your time limit,” says Ronen, who often participates and has watched the force take charge. “It is truly not an exaggeration to say that their work is extraordinary.”

For Ruth Barajas, who is on the labor committee, runs the Resource Hub, and is also director of workforce and education programs for the Bay Area Community Resources, the task force works because of what she witnesses on those Monday morning calls. “It doesn’t matter if it is an organization, an elected official or someone who works for a state officeholder,” she says. “We’re all held to the same standard of accountability.”

It’s on the Monday calls and on other committee Zooms that ideas become reality. Early on in the crisis, for example, monolingual Spanish speakers lacked information about COVID. Some kept their stores open because public service announcements were often only in English. Some parents wondered how their children would attend school online when they had no internet connection. Susana Rojas, the president of Calle24 Cultural District, and Oscar Grande, who works for Mission Housing, staffed the task force communication committee. They put out Spanish language ads on local radio and volunteers went out to talk to residents. But they had a problem: Information changed so fast that ads and fliers became outdated in hours. Grande talked to Julio Lara, his colleague at Mission Housing.

What would you do, he asked?

Lara understood the problem because he too was having trouble updating Mission Housing’s one-page resource page. Lara suggested a website. Suddenly, he and others became the Latino Task Force’s website subcommittee. Five weeks later in mid-May the website launched with oversight by Grande, Rojas, Tulier-Laiwa and Gallardo (the latter two may not be techies, but they know what it is like to be “linked to death”). When Lara’s work popped up on Mission Local’s social media stream, it was a gift – comprehensive and easy to use. At Mission Local, we understood the difficulty of the task – our own resource page had become unwieldy.

Food came first

Early on, as the task force heard from community-based organizations and Hernandez fielded calls from people in need, it became clear that the weekly deliveries from the San Francisco-Marin Food Bank would not be enough to meet the demand. Hernandez first started handing out food from his garage, but “word got out,” he says, and more people showed up, so he moved to the Food Hub on Alabama Street. By the second week the numbers jumped to 1,000 and by late April the Latino Task Force was handing out 7,000 boxes of food week, working Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays with 113 volunteers. Hernandez spent hours between pantry days making calls to find new donations, but often food – steaks, bread, milk – arrived unbidden.

The Food Hub solved problems as they came up. Workers discovered that Latinos were coming from across the city and many were too old to haul their bags back home. For the elderly who lived nearby, the task force could buy carts, but some came from as far away as Bayview and Richmond. At last count, the Food Hub delivers 300 boxes of food a week packed into the back of someone’s truck.

This week, more than 10 volunteers sacked beans, while others packed milk into the boxes and moved pallets stacked with other donations. A group of Ambassadors on loan from the city helped organize the line at the front. That line was actually several. One line doubled around Alabama to 20th, and down Florida to 19th to swing back up Alabama where the boxes would be handed out. A separate line formed on the west side of 19th Street and could be followed west on 19th to then swing north on Harrison Street all the way past Mission Cliffs to 18th Street.

Cara a Cara at The Hub

Early on, it became clear that those on the line had other needs. Where could they get financial help? Did they qualify for food stamps? Unemployment? And if they qualified, how did they fill in the forms without a computer? The pandemic required the staff of community-based organizations to shelter in place. How could the task force safely offer what Barajas calls cara a cara attention – the face to face assistance that the couple I had seen standing outside of the social service agency in March so wanted?

Enter the Mission Vocational School, a grand beast of a building at Alabama and 19th Streets where the task force was already handing out food. More than 100 years old, the building nearly slipped away from the community after its board of directors entered into an option-to-buy agreement in 2013 to sell part of its 35,000 square feet. At considerable expense, Gallardo, Tulier-Laiwa and others managed to save it in 2017. “The soul of this building belongs to the community,” Tulier-Laiwa told Mission Local at the time.

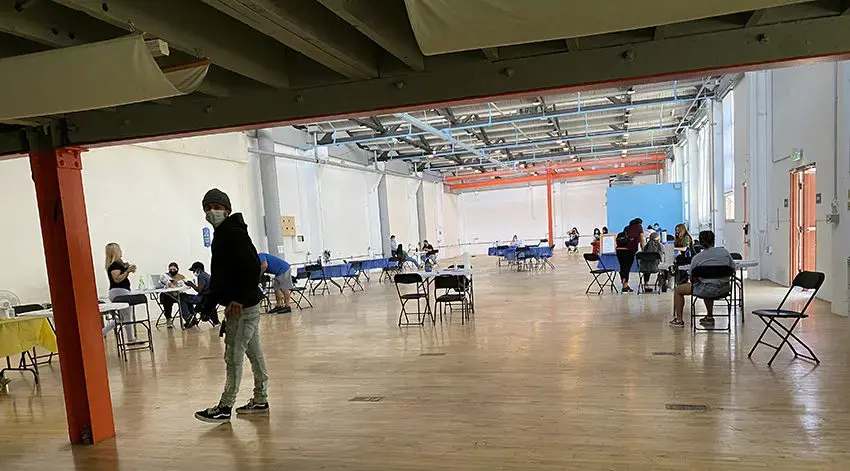

Today, it’s called the Hub – a beehive of frantic yet controlled activity where Mission residents can safely get the personal attention they need.

The section that would have been sold now houses an 18-foot refrigeration unit that stores all of the food pantry’s provisions. Even better, up a flight of stairs is a huge open room with large windows where people pour in for help—and get it. On a Thursday in mid-June, when Barajas showed me around, her staff had already registered more than 1,000 people on the food line who needed more than sustenance.

She pointed at the phalanx of tables: Medical’s back there, housing there, Cal Fresh (food stamps) there, unemployment there and so on. At each table a city worker, a staff member of a community social agency or a paid volunteer sat across from their clients, getting them into the programs they desperately need.

Edgar Gonzalez, an immigrant from El Salvador, had always managed to support himself and his family, but when the pandemic hit, he lost his job with the Yellow Cab Company and was at a loss. Word of mouth led him from the Bayview to the line on Alabama Street and soon workers got him signed up for family relief, a debit card, and food stamps. “We’re generally pretty okay, maybe not doing well by other people’s standards, but successful,” said his son Zair who pre-pandemic worked for a company cleaning the tech buses that shuttle people from the city to Silicon Valley and is now a paid volunteer at the Hub. This was another discovery at the Hub – many residents had never used social services. With the pandemic, they needed them.

The operation runs with borrowed staff from the city, community-based organizations, and newbies. Thanks again to Davis at the Human Rights Commission, the Latino Task Force hired 25 workers to help at the Resource Hub, the Food Hub, and elsewhere.

Many are likely the next generation of community activists. Take Jacky Carrillo, a 20-year-old who started at the food pantry and now helps people get financial support. “This has given me a great, great opportunity to be there for my people,” she says. When she was 13, her mother was deported to Guatemala, but this isn’t a fact she divulges to plead hardship. Instead, because she sees her mother during the summers in Guatemala, “my Spanish is pretty fluent.” She credits that skill for moving her quickly from lifting food boxes into training. What kind of problems do people come in with? “Workers haven’t even been given termination letters,” she says with the outraged tone of a 50-year-old. Workers need that document to get certain benefits, so Carrillo has figured out how to get around that by drafting her own letter explaining the person’s predicament.

A collaboration with UCSF researchers and doctors

In early April, UCSF researchers and doctors at San Francisco General Hospital watched aghast as the Latinx population, generally, 40 percent of its patients, climbed to 80 percent – nearly all with COVID-19. UCSF researcher Dr. Diane Havlir, wrote in an email that they wanted a study “to understand COVID-19 transmission at the community level, in an affected community (in the backyard of where I work at SFGH) and to use the information to both help the community and to advance the science.”

The question was, how to pull it off. One of Havlir’s first calls was to Diane Jones, a retired HIV nurse she knew well and someone with deep roots in the community including a long-time friendship with Gallardo. They knew one another through LocoBloco, a drumming and arts group that has been around for more than 26 years and has turned many a Mission youth into a drummer. It wasn’t long before UCSF was talking to Supervisor Ronen and the Latino Task Force.

The idea met with some resistance. Would this be top-down? Why only one Census Tract? Why a study and not just testing? Trust – the community’s trust in Gallardo and Gallardo’s faith in Jones – won out, and the Latino Task Force jumped on board. “Everyone switched into emergency mode, thinking we have to get this done now,” said Jon Jacobo, head of the task force’s health committee, who marshaled more than 300 recruits to distribute fliers and go door to door in the district to talk to residents. At Mission Local, we too had heard resistance from residents, so getting a visit from locals who spoke Spanish and could answer questions meant that more people were likely to show up for tests that would then be used to measure indicators such as the prevalence of COVID-19 in the Mission, the population most impacted and the strains of the virus.

Lopez, the 30-year-old from the Board of Education, cut through the school district’s bureaucracy to use school sites. “It was probably the most persistent I’ve ever been with the superintendent,” said Lopez. “We had to get legal involved, contracts set and then the same department on” UCSF’s side. How did she manage it? “Non-stop calls.”

Jones thinks she may have gotten the first call from Havlir as early as April 1. By April 25 the testing had begun. Over four days, nearly 4,000 residents and workers lined up to get tested for COVID and antibodies. The UCSF and Latino Task Force collaboration was prepared to support those who tested positive with care and financial support to quarantine. Still, they were surprised by the demographics of the 83 who tested positive: 95 percent were Latinx, 30 percent of those lived with more than five people, and 89 percent earned less than $50,000 a year. Many had no primary doctor. Only one of the 83 was white and two were Asian.

“If you work at San Francisco General Hospital,” said Dr. Carina Marquez, also from UCSF, “you know about all of the health inequalities, but still the disparity was surprising.” Each person, she said, had a unique but similar story – challenges in following through with a quarantine, crowded households, no financial safety net, limited English.

By dint of its own work, the Latino Task Force also had a new ally – researchers and doctors at UCSF and General Hospital. The results could not be ignored and new policies followed. The city opened up unused hotel rooms to those who tested positive. The test results – that 53 percent of those who were COVID positive had no symptoms – indicated a need for more low-barrier testing to prevent the spread. To get more people to test, the study demonstrated that the city would have to assure them that they would have financial and medical support.

The data gave Supervisor Ronen what she needed to get the city on board with her Right to Recover safety net. By late June, Ronen’s program had $2 million to offer up to four weeks of financial support for residents and workers without a safety net. That is enough to help some 1.500 families, but everyone knows the need is likely to be much greater – the research made that clear because it defined who was most impacted by the virus.

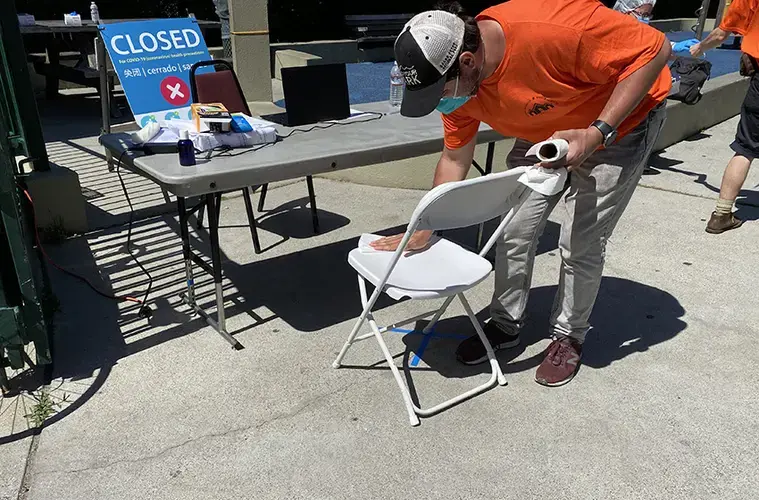

This week, the task force opened a new mobile testing site at Alabama Street – exactly where workers and residents now go and can also be connected to services. Marquez and Jacobo agree that the city still has a long way to go in getting essential workers to take the COVID test. Something, they predict, will have to be worked out with employers so that workers know they will have financial support and a job after they recover.

Preparing for the long term

Just as the coronavirus shows no sign of abating, the Latino Task Force is gaining steam. On a recent Monday morning call with more than 30 community-based organizations, legislative aides and someone listening in from Rep. Nancy Pelosi’s office, Tulier-Laiwa allowed a quick “Las mañanitas” to Hernandez, who would soon celebrate his 64th birthday, and then reminded speakers they had one minute to present.

A dizzying number of projects are underway in housing, worker protection, possibly a second Hub site, and gathering parent input in how schools should operate in the fall. Already this summer the Latino Task Force and community-based organizations such as Dolores Street Community Services and the Day Labor Program helped to revamp the way the city conducted a block-by-block needs assessment of the Mission District. At their behest – and unlike the earlier study done in the Tenderloin – the SFPD was not invited to walk along to do the assessment, more community-based groups were present, and the assessors engaged with the homeless population to ask homeless residents what they needed. That report will be out as soon as this month.

Gallardo, meanwhile, had recently gotten the results of the city’s affordable housing lottery and she didn’t like them. After winning the lottery, too few Latinos cleared the approval process, she said. “Is it a requirement or a removable impediment that applicants are disqualified for bad credit?” she wondered. She was ready to dig into the details and find out.

In many ways, what is happening in the Mission is a reminder of what John Barry, the best-selling author of The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, said about the San Francisco of 1918.“Trust in San Francisco did not disintegrate in the community function,” Barry said in a recent interview on UCSF’s Grand Rounds. “It met the challenge as a community trying to come together.”

In 2020, history is repeating itself, for worse but also for far better, right here in the Mission District.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.

Education Resource

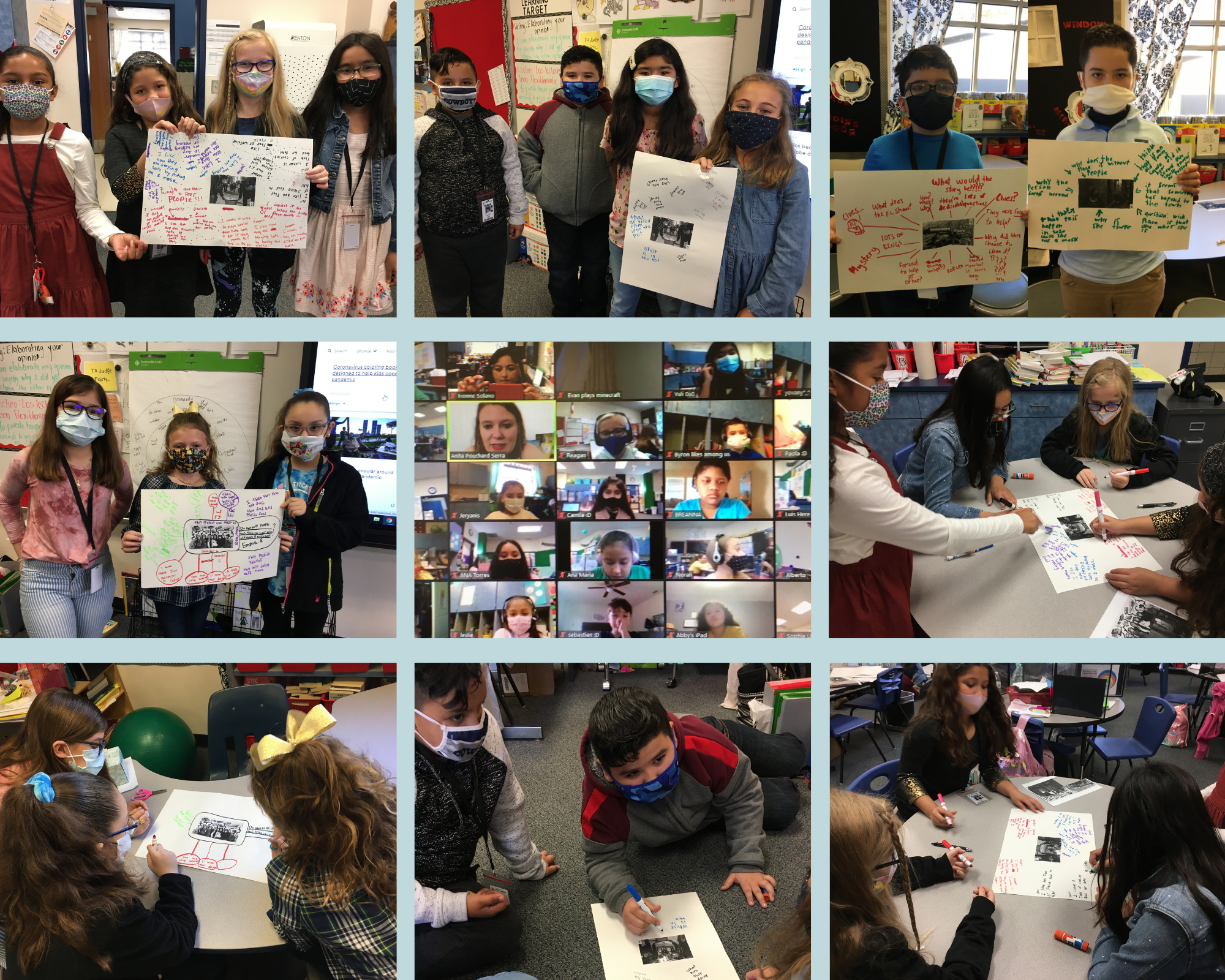

Illustrating Our Community: Analyzing and Crafting Illustrated News Stories

This unit was created by Ena Dallas, an Art and Theater teacher at Oakland Technical High School in...

Education Resource

The Impact Of The Pandemic In Local And Global Contexts—Understanding My Role In My Community To Change The World

This unit was created by Ivonne Solano, a fourth grade bilingual teacher in a two-way dual language...

- View this story on Mission Covid