Nur Amin Rahman, a 44-year-old Rohingya from Sittwe, Rakhine State, Myanmar, now lives on the north side of Chicago, in an area known as Little India. In this part of the city, each block brings diversity, from Asia to the Middle East and Africa.

When we met on a beautiful sunny day, Rahman was dressed in blue pants with a white shirt. “I sit here every afternoon with my Indian tea and have a few smokes and watch people walking down the street with their families and imagine I am with my family,” Rahman said. “Then I am off to drive Uber all night.”

Rahman continued in a broken voice, “My wife left me when I was in the camp. She wanted me to go back to her, but I had no choice because of my stateless status, and I miss my daughter terribly who remains with her mother in Thailand. All I wanted in my life is to taste freedom. I didn’t know when, how, where, or ever in my life I could move around with my heart open without having the fear of being chased by police.”

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

The persecution of the Rohingya in Myanmar (formerly Burma) that began in the 1970s led to the exodus of many refugees. Decades of Myanmar military’s systemic torture caused the Rohingya people to suffer.

“Sittwe is the capital of Rakhine State where we had a beautiful big wooden house in the heart of the city with massive land,” Rahman said. “My family was very powerful politically and economically and everyone knew us as the ‘Suadda Somoni’ family.” Suadda Somoni is Rahman's grandfather's name.

The Rohingya had control of their own lives around the urban areas in Sittwe before the 1982 Citizenship Law, when Rohingya were made stateless. Since then, they have been denied freedom of movement, access to social services, and education.

When he was 5, Rahman and his family moved to Yangon, which served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006. Rahman started his school there but couldn’t continue after sixth grade as he took part in 1988’s nationwide strike. Thousands of students, Buddhist monks, civil servants, and ordinary citizens protested in cities, towns, and villages across Burma to demand a transition to democracy and an end to military rule.

“There was a sense of unity. The volume of those protests shocked the government, which then deployed troops to quell the protests with force,” Rahman told me. “Hundreds of peaceful protesters were killed and wounded.”

Rahman and thousands of students fled to Thailand at the end of 1988. There he met a Thai-born Rohingya girl whom he married in 1996, and they had a daughter. Because he had no documentation, he was tormented by the police and lost his clothing and street-food stores. “I was put in jail many times and when I got released, I started all over again,” Rahman explained. “I thought I could escape the harshness in Thailand and crossed the border to Yangon to see my mother in 2004, but the situation was worse than before.”

Rahman joined his wife and daughter in Thailand in 2010. He traveled on a fishing boat with hundreds of refugees to Malaysia, where Rahman worked as a taxi driver. But every day the police would take his money. He could not report any of the incidents because of his statelessness.

“If I went to the police station I would be put in jail, and it simply means that I wouldn’t have a chance of getting bail and could not be deported back to Myanmar,” Rahman told me. “I would rot indefinitely.”

Rahman learned about Australia and thought it would offer a better life. Smugglers arranged the border crossings from Johor Bahru, Malaysia, to Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia, in a small fishing boat in 2012, but life had another plan for him. Rahman was arrested by the Indonesian police and transferred to immigration detention in Manado, close to the Philippines, where he was detained for two years.

The detention center was small, and there were more than 400 people including prisoners, families, refugees, and asylum seekers. “It was on top of a mountain. The view was spectacular from our tiny rooms,” Rahman said. “I didn’t sleep a single night like most others as we didn’t have to see the officers looking at us like criminals. I watched people walking up and down the hill every morning and told myself that I would be one of them one day.

“It really ruined my human spirit as I was surrounded by beauty but I was not allowed to experience any of it,” Rahman said. “It felt like an intentional mental torture to crush our human spirits, especially when I was stripped, and the guards searched my whole body.”

After two years and several interviews with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Rahman received refugee status. He was released in Makassar, about a two-hour flight away. He was free in the community, but was not allowed to leave the city.

“I learned that my brother with his family, my mother, and sister with her family were in Jakarta,” Rahman said. “I left to join them and became illegal again as I was only allowed to stay in Makassar.”

Ten of them including young children were staying in an empty and small room provided by people smugglers. They called the UNHCR office for days to apply for refugee status, but there was no response.

“There were only two Rohingya interpreters in the whole county, and it was almost impossible to get translation help,” Rahman said. “Thus, getting on a boat to Australia was the only option for us to find safety.”

They had to pay around $20,000 to make the boat trip, but they didn’t have enough money. Rahman said, “My mother and sister sold their wedding gold to the people smugglers, which was heartbreaking because in our Rohingya culture, wedding gold has a very special value, but we were so desperate to rid ourselves of the label of statelessness that we took the boat journey to Australia with the hope of a future in 2013.”

One night, some smugglers came and asked them to get in the car. “It was like you always had to be ready for any type of situation,” Rahman said. “The smugglers drove for two hours and left us in a jungle with other refugees. Four trucks came and it was like a war zone because getting on those trucks meant we would see the boat to Australia.

“We managed to get on the truck and it was like you were loading the truck with animals,” Rahman told me. “People urinated and vomited on each other, and babies almost stopped breathing.”

When the trucks stopped at a mountain, everyone started jumping out and ran down the hill to get to the boat. Rahman and his family managed to come to where many locals were waiting with small canoes to take the refugees to the fishing boat.

Rahman said, “The locals took all of our belongings just before we got on the boat and all we had was a small space to sit on each other with no water or food.”

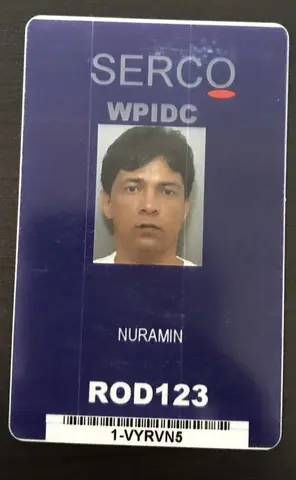

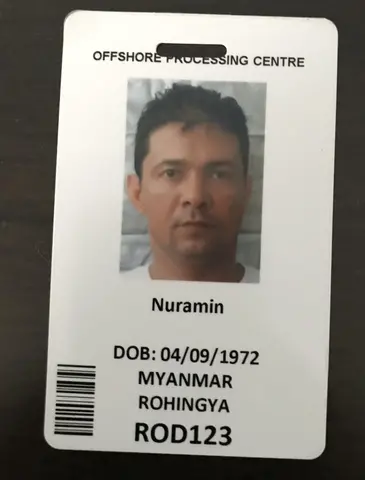

They reached Christmas Island, an external territory of Australia, in October 2013 after floating for six days. They were told by the Australian immigration officers that the refugee policy changed and anyone who came by boat would be transferred to the country’s offshore detention centers on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, or the island of Nauru. This shattered their hearts.

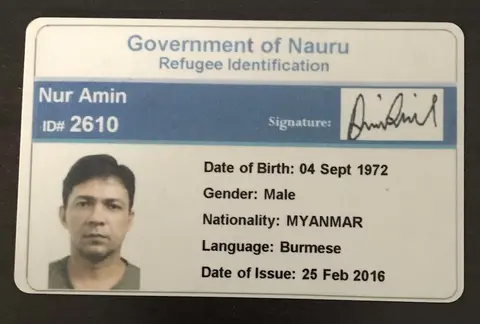

Rahman, his sister, her children, and his mother, who was more than 70-years-old at that time, were transferred to Nauru after some days, but Rahman’s brother and his family were allowed to stay in Australia.

Rahman said, “I feel sick in my stomach when I think about how Australia treated my old mother. I begged the authorities not to send her to Nauru, but they didn’t listen.”

“My mother couldn’t sleep at night,” Rahman told me. “The guards patrolled our accommodation all the time and the sound of their boats and radios scared her. She felt like she was in Myanmar, and the military would take her family away from her. The guards were a constant reminder of her past trauma. She could barely move but she was not given more than five minutes to have a shower in Nauru.”

Rahman’s 50-year-old sister, one of her sons, and her mother became extremely sick after a few months. They were transferred to Darwin detention center with Rahman to look after them. “Our names were on the medical treatment list, but we didn’t receive the medical attention we required,” Rahman explained.

“A lot of Australian security guards came one night at around 2am,” Rahman said. “They grabbed my mother’s shoulders like animals, which I relive every night. I can never forget the sentence that came out of my mother's mouth at that time: 'Oh Allah, why did you send me to this world as a stateless person and why didn’t you give death in my mother's womb?”

They were in Nauru again after nearly a year. “I became numb from that day and didn’t feel anything anymore,” Rahman said. “I came to Australia to be safe, but this nation dehumanized me and my family more than I can describe.”

Rahman was interviewed and accepted for resettlement by the U.S. following the agreement the Australian government made with the Obama administration to take several hundred refugees and asylum seekers from Manus Island and Nauru. He was ready to come to Chicago and was told he would never be allowed to go to Australia.

“Why would I ever want to step on Australia’s soil?” Rahman said. “I was humiliated; my mother was treated like trash.”

Rahman was resettled to Chicago in June 2018 after experiencing five years of physical and mental torture in the Nauru detention center. He thought his sister’s family and his mother would follow him, but they were sent to Australia randomly. Rahman told me, “I was shocked, and my heart was broken into pieces knowing I would not be able to visit my mother again.

“Two of my brothers and their families, my sister’s family, and my mother are living in Sydney, Australia, and I am left alone in grief in the U.S.,” Rahman said with tears in his eyes.

When refugees arrive in the U.S. through the resettlement process, the Reception and Placement program supplies a very small one-time payment per refugee to the resettlement agencies across the country. The initial goal of the resettlement process is to help refugees become economically self-sufficient by finding a job within the first three months of their arrival.

Rahman explained, “I didn’t know anyone, the system, or the country. My caseworker put me in a food factory job as a dishwasher in just one and half months of my arrival.”

Rahman didn’t fully understand how his gross income would affect his eligibility for government health insurance and other assistance.

“I developed so many illnesses when I was on Nauru such as my frozen shoulder, back pain, and serious toothache,” Rahman said. “I wanted to be happy to be free after almost a decade of detention life, but I almost forgot how to be independent and I was expected to function within a month like a normal person.”

Rahman thought of dying many times as he didn’t have any clue how he would survive with his minimum wage job where he only had around $1,050 after all the deductions. He couldn’t make ends meet and each month borrowed from others to survive. He shared a one-bedroom apartment with four other Rohingya men and shared their beds to sleep. He has not had a stable place since he has been here.

“It was important for me to work because it distracted me from thinking about my past trauma,” Rahman said.

Rahman left his dishwasher job and worked at the O'Hare International Airport as a cleaner. He found another job at the Lincoln Hotel where he became the team leader. He was offered a better opportunity at the Langham Hotel where he worked until March 2020. He lost his job because of COVID-19 and has been unemployed for more than a year.

“I wish I knew the support system here, I would have been better prepared to support myself,” Rahman said. “It is hard for me to trust anyone at this stage of my life.”

Hundreds of young adults and men Rahman’s age work odd hours. When they come home after 10-to-12-hour shifts to sleep, they don’t have a bed or any privacy as they share their tiny apartment with multiple people. They don’t have anyone for emotional and mental support. Attending a social event is never possible because of their work. Their downtime doesn’t match with others.

Rohingya are relatively new to the U.S. So many young men come here alone, but there is almost no chance for them to have a family because there aren’t many single Rohingya women. Marrying a woman from another culture is not welcomed, and their lack of English doesn’t allow them to make new friends. The idea of bringing a Rohingya girl from a refugee camp like Bangladesh or India is almost impossible because they are stateless and don’t have a passport to travel.

The trauma that many Rohingya experience on multiple levels is passed down from one generation to the next. Others, like Rahman, suffer oppression, family separation, and humiliation in detention centers as well. They do not seek any treatment because their symptoms are emotional and mental which are not known as illnesses in the Rohingya culture. There is no terminology in the Rohingya language to explain them.

“I am free and have legal papers, but everything feels meaningless as I have no one to share it with,” Rahman told me. “I feel like I live in a world of delusions. Freedom is beautiful, but there is emptiness, and the consequences of statelessness continue to live with me.”