A dead black calf is dumped from the back seat of a Toyota Corolla. The game ball, in other words, has arrived. Deflated. All the intestines have been yanked out and the head and hooves sawed off, to avoid cutting the hands of the 40-odd horsemen warming up their stallions for a buzkashi battle, here on the bone-dry steppe of northwestern Afghanistan.

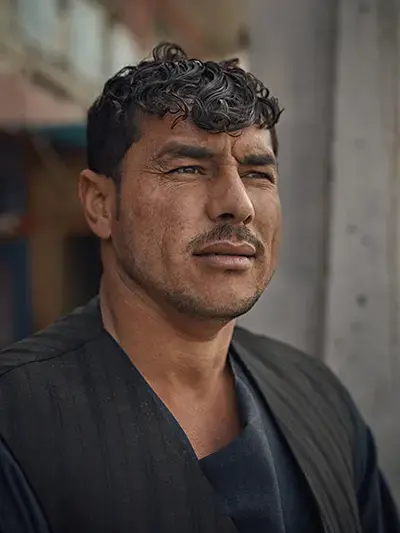

Jahangir is a 38-year-old champion from Shiberghan, a sprawling district of 160,000. He steps down from the grandstand into hard sun. Draped in a silk riding robe and clean-shaven but for a faint mustache, he walks with the bull-necked swagger of a man known to all by his first name. The arena floor—the size of three football fields, walled off to keep the horses from bolting—is beaten down from five months of play. Jahangir’s groom unfurls a blanket and helps him change into match attire: quilted gray jacket and pants, layers of wraparound padding, and high leather boots reinforced with wooden stakes, to keep his shins from snapping under the force of the one-ton beasts that will soon be crashing into him. He swaps his turban for a telbek, the fur-trimmed hat favored by his Turkic ancestors. An AK-47-wielding bodyguard, a war veteran on crutches, and several boys watch the ritual in rapt silence.

Swinging onto his mount, Jahangir struts out to join the ragged mix of riders donning secondhand judo jackets and Russian tank helmets. They line up and pay their respects to local VIPs and fans (all male), then implode into a horse-powered meat grinder, fighting to get within arm’s reach of the calf. To win a cycle of buzkashi, a player, while remaining on horseback, must bend down into a maelstrom of thrashing legs and teeth and snatch the roughly 100-pound carcass from the ground, sprint around a flag at the far end of the arena, and drop it inside a chalked circle, all while opponents do everything they can to steal it from his grasp. Sometimes teams compete head-to-head, but usually it’s every man for himself. Matches last about two hours or until the supply of calves runs out. Deaths are rare, but fractured limbs and nasty cuts are inevitable.

During today’s match, one of the first players to score approaches the stands with blood seeping from his eye. The announcer shouts “Long live Gholam!” into a megaphone. The player nods, tucks a $20 cash prize into his jacket, and turns back toward the scrum. The game is rumbling again at midfield, folding into itself and spitting riders back out, only to see them whack their horses’ flanks, rear up on hind legs, and thrust once more into the chaos of flesh and bone.

This is Buzkashi, the national sport of Afghanistan. The word means “goat grabbing” in Persian, but goats are seldom used anymore because of their tendency to tear apart. Though buzkashi is often compared to polo, easy analogies don’t fit. No mallets or sticks are involved, and there’s nothing remotely elegant or aristocratic about it.

Think of buzkashi’s place in Afghan culture this way: if America’s most beloved professional sport, football, offers viewers the spectacle of ritualized violence, buzkashi is closer to all-out combat, a contest stripped of excessive rules and play stoppages. Instead of billionaire owners, top riders and teams are often bankrolled by former warlords with a lot of blood on their hands. Some of these men still want to destroy each other—and might try, were it not for political and financial incentives to maintain a veneer of stability. In lieu of direct conflict, mutual hostilities are sublimated into buzkashi, a wildly popular proxy contest where reputations are made and broken.

Jahangir’s renown as a chapandaz (buzkashi player) spans northern Afghanistan, thanks to a swashbuckling style that blends raw power and technique. On horseback, he maneuvers his 240-pound bulk with the ease of a man half his size, able to swivel and dive and pick up a calf with one hand. Several local aficionados—most of them Uzbek—told me that he’s the best in all of Jowzjan province, and therefore, to them, the best in the land.

But on this warm March afternoon in Shiberghan, near the end of a tough five-month winter season, Jahangir hangs back from the action as his younger brother, Najibullah, and eldest son, Akbar, take turns winning play cycles that have the slack feel of a pickup game. Fans squat in the half-empty stands, the crack of sunflower seeds audible as the match grinds on.

The lone flash of Jahangir’s dominance comes when a Turkish diplomat arrives with a detail of gunmen. Turkey, a major investor in the region, helped pay for the upgrade of the local buzkashi grounds, as well as schools and a new mosque. Jahangir approaches the stands to greet the visitor. Then, flaunting his status, he barrels into the fray and seizes the calf. Whip clenched in his teeth, he charges through the circle to claim the highest prize of the day: $50 cash. For the rest of the match, though, he looks bored. Pocket money and coffee mugs stamped with the Turkish flag are hardly worth the effort.

“When the general is around, the competition is much better,” Akbar says near the end, lamenting the dull level of play. “Right now we’re just keeping the game alive.”

The general is Abdul Rashid Dostum, 63, the godfather of Afghanistan’s Uzbek minority, a leading buzkashi sponsor, and the nation’s current vice president. Once a street-brawling gas-field worker, he rose from obscurity to become Afghanistan’s most notorious warlord, through legendary feats of battlefield bravery, butchery, and opportunism. In the 1980s, as a militia commander under the Communist regime, he fought against the U.S.-backed mujahideen. He allied with Islamist radicals during the civil war, switching sides several times before joining the Northern Alliance and fighting alongside U.S. Special Forces on horseback to overthrow the Taliban government in 2001.

For a time, Dostum was America’s man in Afghanistan, a hard-charger who got things done. But in the early aughts, as the U.S. ramped up its nation-building efforts, American officials tried to sideline him for reckless behavior and alleged war crimes—including the killing of several hundred surrendered Taliban prisoners who were suffocated and shot inside metal shipping crates in the desert. For his part, Dostum has bragged that he has a Ph.D. in killing militants.

If the general has a soft spot, it’s his love of horses. Once a chapandaz himself, he recruited riders to his first militia campaign and led epic cavalry charges against the Taliban on his favorite white mount, Sorkhan. War spoils enabled him to become one of the country’s top buzkashi sponsors, with his own team and stables stocked with stallions imported from Central Asia. His affection for the sport is so well-known that the Taliban once tried to assassinate him by sewing explosives into a saddle.

In the past, on most Friday afternoons in winter, Dostum could be found holding court on a sofa at the center of the grandstand in Shiberghan, handing out $500 prizes—or, if he was feeling especially generous, the keys to sport-utility vehicles. Not this season. For the past four months, the general has been holed up in one of his mansions, hundreds of miles away in Kabul, the Afghan capital, fighting for his political life.

In late November of 2016, Dostum’s lust for buzkashi and bullying combusted at the Shiberghan arena. A surreal YouTube clip filmed before a match shows him sobbing in the snowfall as musicians sing a tribute to a pair of his bodyguards, killed three weeks earlier during a Taliban ambush of his convoy in a neighboring province. Emboldened by gains in the south and east, the militants had intensified their campaign across northern Afghanistan. It was the latest of many attempts on Dostum’s life, and he was angry about the lack of support from the technocrats in Kabul.

According to witnesses, buzkashi play began, and a rider sponsored by Ahmad Eschi, a former governor of Jowzjan and longtime Dostum rival, won the first round. The general may have been triggered by what he took as disrespect in his own backyard. Eschi, 63, was called over to Dostum and, according to Eschi and other witnesses, thrown to the ground and punched in the face. In front of a crowd numbering more than 2,000, Dostum stepped on Eschi’s chest and threatened to kill him. Eschi was then taken to one of Dostum’s properties, where he alleges that he was beaten, humiliated, and anally penetrated with the barrel of an AK-47. Eschi shared this story publicly, offering inconclusive medical evidence to support his claim.

Dostum’s camp, which didn’t respond to Outside’s request for an interview, has denied the charges. In late 2016, a Dostum spokesman named Bashir Ahmad Tayanj said the allegations were false. Dostum’s supporters have also claimed that Eschi had been arrested—not abducted—because they believed he was aiding the Taliban.

"Buzkashi means "goat grabbing" in Persian, but goats are seldom used anymore because of their tendency to tear apart. Though buzkashi is often compared to polo, easy analogies don't fit."

Western officials and human rights groups urged Afghanistan’s president, Ashraf Ghani, a brainy former World Bank executive, to take swift action, calling the case a critical test of civilian rule. The attorney general opened a criminal case against Dostum and nine of his bodyguards that is still pending.

Sixteen years after the Taliban were evicted to set Afghanistan on a tentative path to democracy, Dostum’s alleged act of barbarism is emblematic of the power warlords still hold. That he would attack Eschi while serving as vice president exposed both the weakness of the government and the folly of Western countries that endorse men of his repute to build up a credible, functioning state. Such impunity is what gave rise to the Taliban in the first place, and their stubborn grip on every level of authority now poses as dire a threat to the country as the insurgency itself.

Yet it was no coincidence that the general’s outburst happened at a buzkashi arena. The sport may seem like nothing but brutish entertainment. In fact, it remains the best context for understanding a chronically unstable, strategically vital region where power is always in flux and symbolic challenges to authority can spill dangerously out of bounds.

The origins of buzkashi are a matter of dispute. Some historians believe it dates back more than 2,000 years, to the time when Alexander the Great marched through present-day Afghanistan. Others say it evolved as a training exercise for Genghis Khan’s Mongol raiding parties. Whatever the truth, the sport has endured for centuries across the vast and rugged Central Asian heartland, with slight variations.

“Buzkashi, like Afghan politics, features powerful individuals rather than fixed rules,” says American anthropologist Whitney Azoy, author of Buzkashi: Game and Power in Afghanistan, the definitive study of the national pastime. “Norms for both games exist in theory, but the incessant struggle for control—for a carcass or a country—is played with slight regard for the niceties of loyal teamwork or agreed-upon rules.”

When Azoy began his fieldwork in the 1970s, Afghanistan was nearing the end of a peaceful interlude, after decades as a stomping ground in the Great Game between Russia and Great Britain. Buzkashi was still the domain of rural khans whose ability to sponsor days-long events—judged by the quality of the riders, guests attracted, and prizes—was a barometer of social standing. Successful chapandazan became folk heroes, known widely by their first names. The Afghan government seized on the sport to deepen its authority at the provincial level. The traditional one-against-all format, tudabarai, in which riders must break free of the pack and keep control of the calf, was phased out for a more organized form known as qarajai, with teams and flags. But the imposed order didn’t last.

In 1978, a Soviet-backed Communist party seized power in the capital, sparking an armed uprising in the countryside. Moscow dispatched advisers and troops to bolster the regime, while the U.S. and Saudi Arabia ramped up support for the rebels. The following year, according to a report in Newsweek, 50 Russian soldiers were massacred at a buzkashi event in Mazar-e-Sharif, the largest city in the north. A deadly attack at another event moved officials to ban the sport, declaring it “backward.”

More than six million Afghans were uprooted by the Soviet-Afghan War, mostly to Pakistan, and buzkashi went with them. Though some of the best horses were conscripted to run guerrilla guns through the borderlands, top chapandazan competed in the refugee camps around Peshawar. These events were usually sponsored by ambitious mujahideen commanders flush with foreign money and weapons. When the Red Army retreated in 1989, the factions lost a common enemy and turned on each other. As Azoy notes, Afghanistan’s “figurative goat grab became ever more chaotic.”

Over the next three years, Kabul was leveled and another 700,000 people fled across the border. This vacuum spawned the Taliban, a fundamentalist movement that pledged to restore order while forbidding almost everything: Western music, films, singing, dancing, kite flying, even marbles. (Buzkashi was tolerated in some parts of the country.) Then came the 9/11 attacks. The Taliban were blamed for sheltering Osama bin Laden, and America’s attention swung back to Central Asia. Dostum, exiled in Turkey at that time, returned to spearhead part of the CIA-backed Northern Alliance that ousted the militants.

Meanwhile, foreign money poured in. Better security and a windfall of reconstruction funds from the U.S. and its NATO partners helped fuel a buzkashi renaissance, led by commanders and agile businessmen who had thrived in the wartime economy. Buzkashi let Dostum indulge in his favorite hobby and burnish his name as the undisputed guardian of his ethnic kinsmen, on a stage where he was the star and director.

Ahmad Eschi had long defied Dostum’s power over the country’s two million ethnic Uzbeks. The two had been allies under the former Communist regime—and had even started a political party together—but they fell out when Eschi refused to support Dostum as head of a regional militia. Eschi went on to hold top government positions in Jowzjan, and his sons were rising stars on the regional political scene, which represented a challenge to the Dostum family dynasty. More recently, Eschi had started building up his own team, going so far as to host Tuesday matches ahead of the usual Friday competition sponsored by the general.

“What better place to show who’s boss than at a buzkashi,” Azoy told me in an e-mail when news first broke of Dostum’s alleged assault on Eschi. “Again the question is: To what extent can the will of one individual dominate the buzkashi landscape? A real question, because it seems that even in this century, buzkashi remains the most public arena for displays of naked power.”

Big brother–style billboards of the bearish Dostum are everywhere in Shiberghan: in a suit and tie next to President Ghani, praying in white robes opposite the main mosque, reading a book to children. The predominant images are versions of a poster mounted at the city gates. It shows the buzz-cut general in camo fatigues and a flak vest, on the front lines of a gunfight with the Taliban, black eyebrows arched in a wrathful scowl.

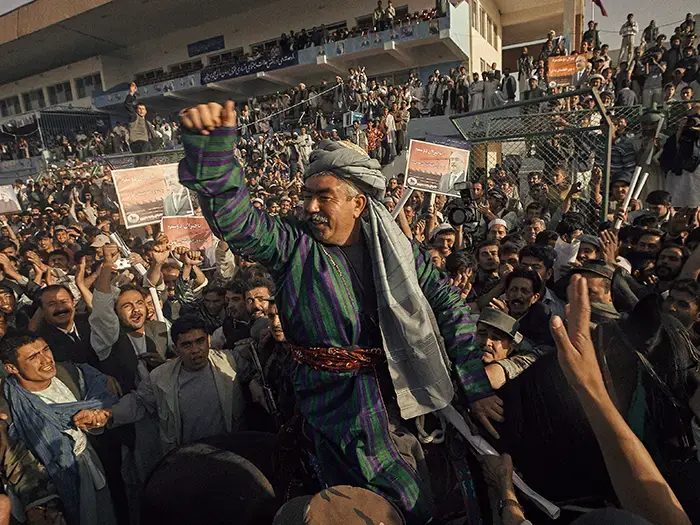

When I first visited the city, in August 2009, Dostum, then the army chief of staff, had just flown back from exile in Turkey. It was the day before national elections, and the general was invited home by then President Hamid Karzai to deliver Uzbek votes critical to Karzai’s eventual victory, despite public warnings from the U.S. ambassador that Dostum’s presence would “endanger much of the progress made in Afghanistan.”

In the center of town I found Dostum’s palace, a square-block property ringed by flesh-colored walls and whimsical cupolas. Gunmen loitered in hundred-degree heat, slung with machine guns and grenade launchers. A group of men near the entrance confirmed that they’d vote for Karzai simply because the general said so. One man said he’d jump down a well if Dostum wished.

“The main reason I came back was concern about the fate of my people in our country,” Dostum told me after I was called inside. “I thought, if Dostum does not come back, my region, the most powerful in the country, will not take part, and this would be bad for the image of Afghanistan.” He claimed that 20,000 people had come to see him over the past two days. “Why did they come to meet me? Because they are afraid the Taliban are approaching. By having General Dostum in the northern provinces, the people will again feel like they are in the belly of their mothers.”

Eight years later, in March of 2017, the Taliban were resurgent in the north and Dostum was AWOL again. Several weeks before I turned up in Shiberghan with photographer Balazs Gardi, at least ten people were reported kidnapped in the area, one of them murdered in captivity. Militants were moving freely in the suburbs. Although Dostum had dispatched 200 gunmen from Kabul to secure the streets, a menacing pall hung over the city.

At the palace, concrete walls now block the side entrance, but the pale pink paint is still here. Inside the courtyard, giant portraits of Dostum are complemented by posters of his eldest son and heir, 29-year-old Batur, who runs a charity and TV station, in large part to soften his father’s image. Short and pudgy cheeked, Batur needs some hardening. A picture of him posing next to his dad with a gun does not inspire confidence.

In the morning, we meet with Haji Gholam Sakhi, the 65-year-old Dostum-appointed head of the provincial buzkashi federation, and his son Asif at a crumbling mud compound that houses their extended family. With a yellow grin, Sakhi says he was never much of a player, but his three sons are all respected chapandazan. At the rear of the courtyard, past hay bales and dried sheepskins, I find a yard sale of gear: jackets, helmets, tactical elbow pads, and shin guards made from sections of PVC pipe.

Sakhi takes me to the stalls where his horses are boarded. He shows me a small brown stallion on the left: until two years ago, it was the only horse he could afford. One day in 2015, at a buzkashi, the general called Sakhi over and asked, “Why do you ride such an un-noble horse?” He told Jahangir to give Sakhi a white mare from his personal stables. It was the same horse I saw Sakhi riding at the buzkashi, shuttling between the scrum and grandstand, happy to be in the orbit of play.

When I ask Sakhi for his thoughts on Friday’s match, he flares up about the pitiful prizes. The season tanked after Dostum left town, and the government is doing nothing to help the struggling chapandazan. “Without Dostum, buzkashi is dead,” he says.

I ask about the alleged violence against Eschi. He pauses and throws me a leery glance. “These are lies, lies created by enemies of the general,” he says. “The horses crashed into the stands, that’s why Eschi was hurt.”

“You know that Eschi is a Communist,” he adds—never mind that Dostum has been one himself. Then the final insult: “And none of his sons play buzkashi!”

I’m trying to shift back to small talk when Asif, who is Sakhi’s middle son, interrupts. “How come the United States is not supporting Afghan buzkashi?” he says. “We are great sportsmen, playing the hardest game, and we get nothing!” Considering how much the U.S. has squandered on half-baked goodwill initiatives, it’s a fair question. I reply that we have a chance to promote the sport in print, which sets up something I’d wanted to ask: Would he be willing to arrange a buzkashi lesson for me? I’d pay, of course.

Sakhi’s mood brightens—easy money is coming his way. “Yes,” he says, smiling, “but you have to be prepared to get hurt.” We settle on a price that includes the cost of a buz, a slaughtered, sewn-up calf. Not too large, I tell him. And no need to invite anyone else.

The next morning, two cars full of men are parked in front of Sakhi’s house. I have unsettling visions of a crowd gathering as chapandazan from the far corners of the province mobilize to compete against a foolish American. I remind Sakhi that this is a training session. “But we must have guests!” he insists, adding that he needs more money up front to buy gifts for them.

“No, no, this is not a real buzkashi,” I say. “Half the money now for the calf, the rest when it’s done, as we agreed.” I hand him $100. He takes it and shrugs.

A fierce wind is licking sheets of dirt off the ground as our caravan pulls into the arena. It’s deserted, to my relief. I take cover in the grandstand and let Sakhi’s grandkids go to work fitting me with buzkashi garb. Asif has an exam this morning, so his grizzled older brother, Gholam, shows up to lead the lesson, sporting stitches on his face from a horse kick. He walks me over to a stallion named Brown. Scar tissue at the corners of his mouth attests to a lifetime of manhandling.

We’re joined by five young chapandazan and Commander Saifullah, a stocky provincial recruiter for the Afghan Army. He had participated in the Friday buzkashi and had fallen off his horse, and he didn’t want to miss a chance to show me up. I’m just winging it, as green as they come. The last time I was on a horse was more than a year before—on a slow joyride through a Cuban sugar plantation.

I climb onto Brown and try to guide him with my hips. He’s unresponsive. A gentle smack on the behind doesn’t help, either. Gholam grunts and shows me how it’s done. Jerking his reins hard right, then left, whipsawing his mount’s head, he tells me to steer “like driving a car.”

The buz I paid for weighs no more than 50 pounds, half as much as the ones used in a normal match, but I can’t pick it up, even at a standstill. After some awkward groping, Gholam grabs my reins, allowing me to get a grip on the buz while trying not to fall off the horse. Instead of heading toward the flag, Brown trots straight into the corner of the arena. Then he lurches through an open gate slot to shave me off his back.

I swap for a shorter horse and snatch the buz without much trouble. Soon we’re bolting across the pitch. I turn around to see Gholam flogging my horse’s rump to make him go faster. I’m in a steady rhythm, head back, savoring the rush of flight—until Gholam’s mount, baring teeth and frothing pink from the harsh work, exacts revenge on my thigh, chomping down hard. The pain is electric, but adrenaline is surging and there’s no stopping us. We round the flag and charge another 80 yards toward the scoring circle, where I manage to accurately drop the calf.

Soon, back in the scrum again, flailing for a grip, heels over head, I feel the graze of a hoof against my beard. Any closer and I’d be missing teeth. The other riders are not so much competing as seeing how hard they can push my limits. After an hour of rough riding, I’m caked in dirt, crunching grit between my molars, aching all over, and totally exhilarated.

Gholam gives me a firm handshake and, in a bit of tip-seeking flattery, says that if I keep training I have promise. I pay out what’s owed to Sakhi. The filthy buz is thrown in the back of his station wagon for dinner. Sakhi is grinning again.

“So now what do you think of buzkashi?” Jahangir asks afterward. We’re late for our lunch appointment at Dostum’s stables, but the champion is amused that I’ve tried it, even more so by my limp.

“It’s much harder than it looks.” He gives me a gap-toothed smile.

During our first meeting at the Friday buzkashi, Jahangir kept his distance. As a confidante of Dostum’s, he was probably wary of foreign journalists using the sport as a way to dig up dirt about Eschi. A phone call from a former Dostum staffer seemed to ease his mind, and he was keen to show us hospitality as a pahlawan, the honorific title given to leading buzkashi players.

Now we’re his guests at Tolai Sawar, an equestrian fortress owned by Dostum, with a commanding view of the arena and surrounding plains. Outside, some 50 horses eat from adobe grain silos, watched by guards in crenellated turrets. We sit on rugs as servants arrive with trays of food: pulao with shards of carrot, freshly picked greens, homemade yogurt, and baby lamb fried in onion, complete with the head. Jahangir cracks its skull open with his meaty hands and offers me a spoonful of brain. “So long as you are with me,” he assures us, “you have nothing to worry about.”

What about something to drink? Balazs and I look at each other—we’re in a strict Islamic country—but it’s clear Jahangir expects company. A bottle of vodka appears and he pours out a round, filling his small tea glass to the brim and shooting it down. We obligingly sip ours. “You’re not drinkers,” he says with a hint of disappointment.

Heaping more pulao on our plates, Jahangir says that the role of a pahlawan far exceeds playing the game. “We must have good morals and be an example to the people.” Sometimes he pays school tuition and medical costs for the poor. He also helps mediate disputes, like the time last year when two men were arrested in a nearby district on suspicion of being Taliban. Family members traveled to Shiberghan to plead with Jahangir, who relayed their message to Dostum. The general asked them to guarantee that their sons were not militants. They did, and the men were released. Jahangir was invited to a feast of thanks.

Jahangir was born in Khoja Doku, the same hardscrabble farming district Dostum comes from. His elder brother died while fighting for the general in the early 1990s, during the civil-war battle for Kabul. Jahangir started playing buzkashi as a teenager and, in his first year competing full-time, won an automobile at an event sponsored by Dostum. His skill attracted sponsors in Shiberghan, and later Mazar-e-Sharif, the epicenter of northern buzkashi, 50 miles to the east.

In the mid-nineties, when the Taliban ruled Kabul, Mazar was the seat of a Dostum mini state. He printed his own money, launched an airline, kept order, and championed women’s rights while cruising around in an armored Cadillac. But in 1995, a rival warlord took power and forced him into exile. He came back and briefly regained control of Mazar, until the Taliban drove him out. Three years later, he stormed back to liberate the city.

With the Taliban gone, Dostum and his arch-rival, Atta Mohammad Noor, a Tajik militia commander, fought each other for northern supremacy. Gun battles between their forces continued until a 2003 United Nations disarmament campaign kicked in. Dostum withdrew to his Shiberghan stronghold, and Noor became governor of Balkh in 2005—an ancient Silk Road town—trading fatigues and a long black beard for sleek suits and carefully groomed stubble.

Under Noor’s heel, Mazar has prospered relative to the rest of Afghanistan, with tight security, smooth roads, and a new rail link to other parts of Asia. Nothing happens without his knowledge. So when two Dostum portraits were removed last March from the city center, allegedly by men driving police vehicles, hundreds of Uzbek protesters raised hell in the streets. The portraits were soon restored, but renewed factional bloodshed seemed imminent.

In this volatile climate, the buzkashi arena has become a potential flash point for real violence. The Noor-Dostum feud barred top Uzbek players like Jahangir from competing in Mazar, while Tajiks stayed away from Shiberghan. And across the north, militant suicide bombers have been attacking buzkashi events with greater frequency, to sow fear among the public.

When Dostum asked Jahangir to lead his team in Shiberghan, Jahangir didn’t think twice. Along with horses from Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, Tolai Sawar boasts a clubhouse with a staff cook, fully equipped gym, pool table, and big-screen TV. Walls are plastered with pictures of Dostum and his favorite roughnecks, including Jahangir, Najib, and other top chapandazan.

Riding for Dostum earned Jahangir up to $50,000 in a good season, but his long-term outlook is iffy. His earnings during the 2015–16 season were less than half what they were the year before. When I talked to him, Naw Ruz buzkashi, a big New Year’s event that usually promised the fattest prizes, was just a week away, but no sponsors had come forward. Now, four months after Dostum’s departure, it was not clear when the general would be back in Shiberghan. His prolonged absence had cut deeply into the riders’ livelihoods and left the door open to saboteurs and schemers who would exploit the slightest advantage—as Dostum himself had done throughout his career.

“Things are disorganized,” Jahangir says. “If there is not one strong man at the top, there will be chaos.” He was referring to buzkashi, but he might as well have been talking about Afghanistan.

With competition in the cities debased by factional politics, the best buzkashi was to be found in the hinterlands. One afternoon we turned north off the highway that connects Mazar and Shiberghan and drove toward the outskirts of Balkh. Traveling through a craggy moonscape, we passed the remnants of towering fortress walls to reach a plateau where a match was under way. The air, thick with hash smoke, was charged by the announcer’s breathless commentary as riders swarmed over the calf, which was invisible in the dust. If not for the parked cars and Kalashnikovs, the scene could have been from a thousand years ago.

Idling on the fringe was Gulbuddin, a Pashtun regarded by many to be the best all-around chapandaz in Afghanistan. With wide, square shoulders and a short neck, he was unassuming except for the huge horse beneath him. He watched as the scrum crashed through a line of spectators and a breakaway pack chased the rider with the calf several hundred yards into an open field. The game drifted for a couple of minutes before the pack stormed back on the heels of two chapandaz, each pulling a calf leg so hard, it looked like the carcass might tear in half.

Finally, a rider managed to wrest away the calf, and Gulbuddin sprang into action. Bolting into a blind spot behind the man, he moved tight inside and deftly reached across his body to grip the calf’s hind leg, then pulled his mount hard right, wrenching the carcass free. The brazen theft, or chakkagir, had fans across the ethnic spectrum—Pashtuns, Uzbeks, Tajiks, Hazaras—on their feet. “Gulbuddin! Gulbuddin!” they howled as he came around for an easy score.

At week’s end, back in Shiberghan, the final Friday buzkashi was abruptly canceled, a fitting conclusion to a disappointing season. Jahangir, Najib, and a handful of Dostum’s top riders were summoned to Kabul to have tea with the general before catching a morning flight back north and driving to a buzkashi near the Uzbek border.

Malik Tatar, an Uzbek militia commander and Dostum ally, had called for a two-day event in the northeastern province of Takhar to celebrate his marriage. The Taliban were active in the area, but with Dostum footing everyone’s travel costs, the chapandazan were willing to make the roundabout journey. In an effort to catch up with them, we booked a morning flight to Kabul, but the only connecting plane had left by the time we arrived.

The trip, we were later told, did not go well. On day one, about 200 competitors turned up, but Tatar provided only one horse for each Shiberghan guest, rather than the customary three or four, forcing them to borrow from locals. Jahangir still won three rounds, and Najib, his younger brother, took the last play cycle. That night the Taliban attacked the district administrative center.

“They heard General Dostum’s chapandazan had come, so they wanted to kidnap us,” a teammate of Jahangir’s told me. Taliban fighters struck again the next day, targeting the buzkashi with two long-range rocket-propelled grenades. There were no casualties, but the chapandazan fled under fire. Gun battles raged into the night between police and the militants, further damaging the host’s reputation.

With several days to spend in the capital before our flight home, we reached out to Dostum one last time, on the off chance that he might be in the mood to break his months-long silence. No go. The general was still holed up in his fortified compound, sleeping past noon and not speaking to reporters.

One man who did grant us an interview was Ahmad Eschi, his alleged victim. Eschi was staying in Kabul’s diplomatic quarter at his party headquarters, just a five-minute drive from Dostum’s place. Sandbags and an armored Humvee guarded the front gate. In the lobby, we passed a campaign poster for Eschi’s son Babaur, a member of the Jowzjan provincial council. Looking regal in an Uzbek turban and robe, his image was accompanied by a horse icon—a symbol used to identify him to illiterate voters at the polls.

Eschi entered with the cautious steps of a senior citizen recovering from illness. He told me he came from a family in Khoja Doku, where horses are at the core of existence and communal identity. “If you have one day in your life, you must buy a horse,” he explained. “If you have two days, you must be armed. If you have three days, you get married. The horse is the priority—they have been life partners of Turkmen since the beginning. It’s difficult to express how much I love them.”

In recent years, Eschi conceded, he had invested in his own team to challenge Dostum’s reign. He was importing horses from Kyrgyzstan, and his chapandazan were getting better, competing head-on against the general’s riders.

The day of the attack, Eschi said, Dostum was already “acting strangely,” pacing around in the snow rather than taking his usual seat. When one of Eschi’s riders won the opening play cycle, Eschi called his team over and told them to lay off to avoid angering the general.

But it was too late. He recalls Dostum shouting at him: “I know what you have been doing. What if I make you the calf and order the players to play with you?”

After getting beaten up on the playing field, Eschi said, he was forced into a black armored vehicle and driven to one of the general’s homes, where Dostum roamed the courtyard, cursing and circling back to punch him more, before ordering him taken to a basement, where, allegedly, he was to be gang-raped. Eschi alleges that Dostum’s men, unwilling to perform the act, instead shoved part of an AK-47 barrel into his anus. He blacked out. For the next five days, he was locked in an empty room, bloodied and pantsless. On the third day, he was allowed to wash himself; he was unable to recognize his own swollen face in the mirror. He was handed over to local intelligence officers and held ten more days in a detention center.

Eschi suspected that this was done to allow his wounds to heal in private, with the hope that shame would shut him up later. It didn’t. In December of 2016, he appeared on national TV to share his sordid account—a taboo-breaking move in a macho, conservative society. “According to laws of the Afghan constitution, he should be punished,” Eschi said of Dostum. “If nothing happens here, I will not rest. I will take this to the international criminal court if I must.”

For six months, efforts to bring Dostum to justice went nowhere. He bucked the attorney general’s requests to appear for questioning, and when police surrounded his Kabul mansion to arrest his guards, the general called in reinforcements and seized checkpoints on a strategic hill overlooking his property. Afghan officials dared not force a confrontation, fearing that Dostum would retaliate by unleashing violence in the north. But a well-placed source in Dostum’s camp told me that he would soon leave the country in a face-saving move, likely under the pretense of seeking medical treatment.

In late May, the general decamped for Turkey on a nighttime flight, ending the embarrassing standoff at a dire moment for Afghanistan. A month after we left, Taliban suicide bombers disguised as army personnel struck a base in Mazar and killed more than 140 soldiers, the deadliest attack against Afghan forces since 2001. Then, on May 31, a massive truck bomb went off during morning rush hour in Kabul’s heavily fortified diplomatic quarter. The blast claimed more than 170 lives and injured some 500, the worst strike yet on the capital.

Now under siege by the Taliban and Islamic State, roughly half the country is controlled by insurgents. After two previous administrations spent 16 years to fight the longest war in U.S. history—at a cost of $800 billion and some 2,400 American lives—President Donald Trump recently pledged to send thousands more reinforcements to avert the collapse of a government widely viewed as illegitimate. He has vowed to “fight to win,” but Afghans know better. For many, the state’s failure to hold Dostum accountable for the Eschi assault is proof that warlords are as strong and corrupt as ever, the rule of law a farce.

Public distrust has been compounded by the immunity granted to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, an Islamist militia leader behind some of the worst atrocities of the civil war. Protesters fill the streets nearly every day in Kabul, and many politicians, including cabinet members, are calling for President Ghani and his security ministers to resign.

In an about-face that would be stunning anywhere but Afghanistan, Governor Noor and General Dostum, sworn enemies for decades, have since formed an opposition alliance of ethnic minorities. Calling themselves the Coalition for the Salvation of Afghanistan, they accuse Ghani and fellow Pashtuns of monopolizing power and have threatened to take control of northern ministries and airports to “paralyze” the government if they are not heeded.

In July, Dostum tried to fly back home from Turkey to lead the insurrection. His private jet was denied permission to land in Mazar, on orders from the central government. But it’s just a matter of time before he returns.

The buzkashi is on again.