NAIROBI, Kenya — Kenyan researcher James Miser Akoko stood at the edge of Nairobi’s vast Dandora dump in the late afternoon heat, staring down into a recipe for the next pandemic.

Below him, dozens of men and women scoured a 30-acre garbage pit in a grim version of recycling, gathering deflated soccer balls, soiled plastic toys, filthy clothing and blankets, even abandoned airline food. They worked with bare hands and no face masks, shrouded by smoke from small fires and shadowed by the large marabou storks with which they compete.

Free-ranging pigs, goats and other livestock grazed on refuse, marking time until the day they become food themselves – human food.

A quarter of a mile away, in the neighboring Korogocho slum that shelters 150,000 of Nairobi’s poorest people, Akoko encountered a middle-aged woman laboring over a large, uncovered pot of simmering chicken intestines. These she would sell to passers-by in the slum. Then, as the sun set, she would turn her attention to another source of food and income: an open bag of raw chicken legs and feet, fought over for now by buzzing flies.

As she tended her pot, dozens of marabou storks appeared, circling overhead.

“One task that is still undone for us,” Akoko said, “is to go into the dump sites and catch the marabou storks to see what they are carrying.

“Studies have shown that they’re quite good for the ecosystem because they basically clear the dead stuff – pieces of meat, dead animals. But we don’t know what they are spreading in Nairobi in terms of disease.”

When scientists worry about the next big outbreak, it is places like this they mention: sprawling Third World cities, with large populations of humans and animals living together amid the squalor of dirty water and poor sanitation. Of Nairobi’s 3.4 million people (more than the combined populations of Chicago and Milwaukee), about 60% live in densely-packed slums, sharing muddy roads with goats, pigs, chickens, cows, dogs and rodents.

Imagine a melting pot into which the livestock, the birds, the flies and the people all contribute bacteria and other microbes – a Petri dish for the creation of new threats to human health. Pigs, for example, act as mixing vessels for influenza. They can be infected by both bird and human flu, allowing genetic material from each to combine and form new strains.

A few years ago, researchers at King’s College London imagined how this biology might play out in a slum, devising a hypothetical scenario, in which “poor sanitation and high population densities lead to a new outbreak of virulent influenza.”

Their scenario begins with impoverished residents watching their pigs and poultry fall ill, suffering high fevers and bleeding from the mucous membranes in their mouths and noses. Within a day, animals begin to die. Within a few weeks, the new influenza spreads from the animals to the humans who handle them. And because the residents have lives outside the slum, working in hotels and factories, riding on buses, shaking hands with everyone from aid workers to merchants, the influenza advances beyond the slum.

By the time the World Health Organization sounds an alert, the disease has already crossed continents.

Within a month and a half, the authors wrote, “the virus has spread to nearly 80 million people worldwide. Carried abroad by international long distance commercial flights, the illness leap-frogged out of Asia and appeared in Hong Kong, London, Paris, Marseilles, North Africa, New York, Beijing, Calcutta and Dubai almost simultaneously.”

All told, the influenza kills 140 million people.

It is only hypothetical, of course, though “a plausible situation,” said Kristen Bernard, professor of virology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Veterinary Medicine. “Absolutely, it’s plausible.”

The authors set their scenario in the poverty-stricken favelas of São Paulo, Brazil. They chose the favelas because these areas have a high density of humans and animals living in close quarters, sharing poor water and sanitation.

Much like Nairobi. Or Mumbai. Or Mexico City. Or dozens of similar cities around the globe, all expanding, as the world’s population shifts from rural to urban areas.

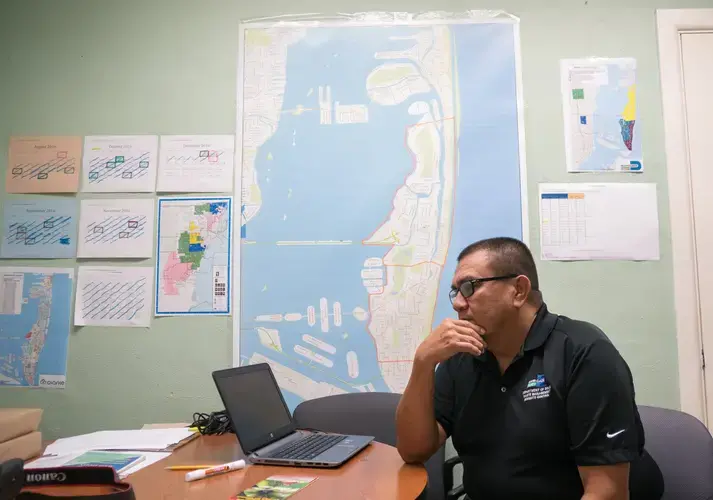

In Nairobi, where the population has more than doubled in 27 years, Akoko’s employer, the International Livestock Research Institute, is not waiting for the next pandemic. The institute is part of a project studying the interactions between people and animals in the city and how those contacts contribute to disease. The goal: to change the conditions and behaviors that put Nairobi at high risk for outbreaks.

“Korogocho is a slum and the ground underneath Korogocho is a (former) dump,” explained Eric Fèvre, a researcher at the University of Liverpool who also works for the institute and leads the project Akoko works on. “These guys (in the dump) they’re exposed to birds and rodents and feces ... Hundreds of people depend on that dump.”

Alongside the dump flows a tributary of the Nairobi River, a waterway so polluted with litter and human and industrial waste that Fèvre called it “basically a sewer full of plastic bags.”

***

Americans seldom see the disease-brewing conditions in Nairobi and similar large cities across Africa and Asia, but scientists say they can no longer afford to dismiss them as problems of the developing world. Our higher standard of living and advanced medical system do not insulate us from diseases emerging halfway around the globe.

The notion that we are safe from distant outbreaks is a “historical misconception” that dates back a century to the days before international air travel, said Amesh Adalja, a senior associate at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

Back then, the U.S. had cholera and yellow fever outbreaks of its own, but faced much less of a threat from infected travelers. Most died of the diseases they picked up overseas before they could return home to spread them.

Today, “a microbe originating in Africa or Southeast Asia can arrive on North American shores within 24 hours,” according to a 2014 report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We’ve already seen the results. Studies say that a majority of U.S. cases of difficult-to-treat, drug-resistant typhoid fever can be traced back to six developing countries.

Last year, a record 213 million international travelers flew in and out of the United States. In 2015, the most recent year for which data is available, more than 29,000 Kenyan citizens visited the U.S.

While air travel now links Kenya and the U.S., offering a path for disease, the countries start out with very different risk profiles. Americans still benefit from basic necessities most Kenyans lack: clean water, good sanitation and mosquito-proof homes equipped with screen windows and air conditioning. The difference in disease toll is staggering.

Each year the U.S. records an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 cases of mosquito-borne malaria, almost all involving travelers from abroad. Kenya records more than nine times as many cases on an average day – some 6.7 million cases a year, including 4,000 deaths.

“It’s a very debilitating disease,” said Bernard Bett, a senior scientist at the Nairobi institute who survived several bouts of malaria during his childhood in the Kenyan highlands. “You get headaches. You don’t eat. You don’t have the strength to do anything.”

Most American children never know the misery of malaria, another reason it is sometimes easy to believe ourselves immune to the pathogens flourishing in the developing world. Still, the U.S. has experienced the havoc that even a single case of a tropical disease can cause.

In 2014, Thomas Eric Duncan showed no symptoms of illness when he boarded a plane in Monrovia, Liberia, bound for the U.S. He arrived in Dallas on Sept. 20 and became ill a few days later – America’s first case of Ebola and its sole fatality.

“The first case of Ebola diagnosed in the U.S. had major cascading effects that rippled through several industries,” said Adalja, the Johns Hopkins researcher. “Every hospital had to augment their preparedness, public health agencies were tasked with monitoring large numbers of those returning from West Africa, airport screening tools had to be developed, and general panic from the public and politicians ensued.”

While our Ebola scare passed, a longer-term problem arrived last July.

A little more than a year after the Zika virus began storming through Brazil and most of Central and South America, the virus arrived in South Florida. It’s not known for certain whether Zika came to Miami on a plane, but once there, it found a home.

“It was not ‘if’, but ‘when’,” said José Szapocznik, a Zika expert at the University of Miami, explaining that the mosquitoes that carry the virus were already in Florida, “up the East Coast, out to Texas and the Gulf areas.”

All the mosquitoes needed were infected people to bite, and they would find them soon enough.

“There is a huge viral reservoir in the Americas,” Szapocznik said, “and we have people coming from that viral reservoir to Miami on an ongoing basis.”

While not a pandemic, Zika offers a case study. From its discovery seven decades ago in a forest in Uganda, Kenya’s neighbor to the east, the virus traveled thousands of miles to the neighborhoods of Miami.

A new disease to test us.

***

Zika arrived last July at the peak of a hot, humid Miami summer.

Tourists and locals were crowding the sandy beaches and bustling, narrow streets of Miami Beach, strolling between stores and sipping drinks under the beaming sun.

For two local women, Yessica Flores and Sloane Borr, it was a joyous time. They were pregnant.

Flores, 38, was nearly three months into her pregnancy; the child would be her second. An immigrant from Honduras, she lives in a colorful one-story home in Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood with her husband, her mother and her 14-year-old daughter, Andrea. The family had just returned from a trip to Honduras a few weeks earlier, and Flores was alternating between responsibilities at home and her job in the cafeteria of a local school.

“I heard about Zika from the time it started in Miami,” Flores said, speaking through an interpreter. “But I didn’t bother with it.”

Borr, 30, lives a few miles northeast in a gated community on the edge of Wynwood. A writer, she works from an office in the home she shares with her husband, Paul, and their dog and cat.

Borr was aware of Zika’s spread through the Americas, but the threat seemed distant. As a soon-to-be mother, she sympathized with the mothers of the infected babies in Brazil. But mosquitoes, though a nuisance, were simply nothing new.

“That’s just like a way of life in Miami, to be covered in mosquito bites,” Borr said. “You don’t think anything about it. You don’t realize that, in other countries, a mosquito bites you and you could be dead.”

Watching Zika more closely than the two women was a man named Chalmers Vasquez, operations manager of Miami-Dade County’s mosquito control team. He believed the region was ready to combat the mosquito that carried the virus. In the past, the department had handled such tasks with ease.

The county had recorded cases of dengue fever in 2010 and 2014, and chikungunya, also in 2014. Both viral diseases are transmitted by the same mosquito responsible for Zika: Aedes aegypti.

On July 15, 2016, Vasquez and some co-workers stopped for lunch in Fort Myers on their way back from a visit to another mosquito control district when his phone rang.

Zika had arrived in South Florida. It was the county’s first Zika case caused by local mosquitoes.

That night, he and his team set their first round of mosquito traps and began monitoring the population.

***

For more than half a century, Zika had kept a low profile.

Discovered in 1947 in a monkey from Uganda’s Zika Forest, the virus spread through mosquitoes in Africa and Asia. Humans rarely got the virus, and the symptoms were so mild that those who did rarely sought treatment.

In fact, Zika seemed the least troubling of the various diseases carried by Aedes aegypti. The others – Chikungunya, dengue fever, West Nile virus and yellow fever – all continue to ravage countries that lack proper mosquito control.

By comparison, Zika had done little damage.

Before 2007, only 14 cases of Zika had been documented in people, according to the World Health Organization. Because only 20% of patients show symptoms, it can be difficult to track the movement of the virus.

Despite the scarcity of symptoms, blood tests showed the virus was actually very common in Africa and had spread to Southeast Asia: from 2% infected in North Vietnam to 75% in Malaysia.

Still, Zika wasn’t a high international concern until a small island in Micronesia, called Yap, began to notice a new illness causing rashes, pinkeye and joint pain. It looked like dengue, but something was different: the fever was milder and accompanied in some cases by pinkeye. In June 2007, lab samples sent to the CDC confirmed the disease was Zika. The stealth virus had caused its first outbreak.

In the end, an estimated 73% of Yap’s more than 7,000 residents were infected.

Soon, the virus began popping up in other places that had never seen it before – places where people had not developed immunity.

In May 2015, eight years after the outbreak on Yap, researchers in Brazil’s National Reference Laboratory confirmed Zika was circulating in their country. Reports of birth defects that would later be linked to Zika infection began to pour in: babies born with small heads and poor eyesight. The babies wailed in almost constant pain.

Zika’s sudden rise to international prominence continues to baffle experts. It is unclear how the virus went from anonymity to, as the World Health Organization called it, a “public health emergency of international concern.”

The global outbreak left scientists wondering how the severe effects of Zika, including the birth defects, went unnoticed for decades.

Some have suggested that in the new areas, there were simply more pregnant women vulnerable to infection. In Asia and Africa, where many had already caught the virus, the only people left to infect were children, and they would have immunity by the time they reached childbearing age, said Sharon Isern, a researcher at Florida Gulf Coast University.

Matt Aliota, a researcher at UW, suggested another possibility: The virus had never infected a population large enough to allow scientists to track the effects.

One other factor could be at play, according a 2016 Nature article by Isern and her colleagues: Dengue.

Lab work by Isern suggests a prior dengue infection could allow Zika to proliferate more in the body, causing the severe infection characterized by birth defects in babies. However, the theory remains controversial, and early research in primates at UW has shown there may be no such effect.

Brazil’s outbreak was curbed, thanks to a wide-ranging strategy of mosquito control – from fumigating 20 million homes, to releasing millions of genetically modified mosquitoes that produce infertile offspring. Even so, the outbreak crossed borders. As of March 2017, 84 countries have reported evidence of Zika in native mosquitoes.

The breeding habits and distribution of Aedes aegypti make it a beast to control, said Vasquez in Miami. Still, the mosquitoes themselves can’t travel very far – only a quarter mile in their lifetimes.

But people can. And so, Zika crossed the ocean and made its way to Miami.

***

In Kenya, the second week of January this year brought a fairly typical burden of disease: 61,000 new cases of malaria (30 years’ worth for the U.S.), and 3,200 cases of typhoid fever (six months’ worth for the U.S.).

On this particular week, though, the challenges facing Nairobi’s health care system were more of the slowly-ticking, time bomb sort: the kind illustrated by the gap between city laws and the lives of city residents such as Paul Mugai Ngage.

Ngage lives in a place that is absent from most maps, a blank space where more than 133,000 people live. Officially, the Kawangware slum does not exist. Neither does Korogocho, where the scavenged goods from the dump are sold. All of Nairobi’s slums are considered illegal settlements.

Yet there stood Ngage, smiling as he gestured across his yard.

“Welcome to my home,” he said, laughing and describing his age as “over 75.”

The little property where he lives belonged to his father, who now lies buried behind the house. Today, Ngage shares the modest concrete home – essentially one large open room — with his wife, six children and “many grandchildren.”

In Nairobi, keeping livestock in the city is illegal, as it is in many large cities around the world. The practice began falling into disfavor in the 19th century, considered unsanitary and a disease risk.

Yet there in Ngage’s yard roamed an assortment of goats, sheep, geese, chickens and the family dog. The jawbone of a dead cow lay in the dirt, just outside the pen where the family’s lone surviving cow was resting. Rabbits and pigeons stared out from a stack of hutches.

“What you should appreciate is that the goats, sheep, the geese, the chickens, all of them are in one area, where they interact,” explained Patrick Muinde, a veterinary research assistant at the Nairobi institute. “A disease which can be transmitted by geese can be passed to chickens with severe consequences.”

Ngage’s yard and the air around it amounted to a microbial stew, a single place in which different species deposited their wastes, bodily fluids, even the tiny droplets that spread influenza.

Many animals have their own strains of influenza.

When they are kept in close quarters, a single animal may be infected with two different strains. As a result, segments of genetic material from one strain can mix with those from the other to form something new, a process scientists call reassortment.

This is how new pathogens are born.

None of the conditions in the yard are unique to Ngage’s home, but common in the slums, where poverty and tradition dictate behavior. For poor families, soap is a commodity that must be weighed against necessities such as water, food, shelter and school fees for the children.

“They’ll tell you, ‘I’ve not been washing my hands. I’m OK. What does it matter?’” Muinde said of the residents.

Here open-pit latrines — slits in the ground that must be crouched over — are a luxury. Those who do not have one must pay 5 shillings (roughly 5 cents) each time they need to go. Some lack the money, and at night, women feel unsafe venturing out in the slums.

So, residents have devised an alternative, the so-called “flying toilet.” The poor use plastic bags for their excrement, then throw the bags as far as they can.

Although human waste is a source of many diseases, including cholera, typhoid and hepatitis, discouraging residents from resorting to the use of flying toilets is not as simple as it might seem.

“People don’t use flying toilets because they want to, but because they don’t have any choice,” said Fèvre.

Residents in the slums have made the same point while admitting to researchers that they have eaten airline food collected from the dump, or chicken feet from the floor of a slaughterhouse.

“They know there may be risks,” Fèvre said, “and they don’t like those risks, but they don’t have a choice ... So it is a survival strategy, and changing that means changing the root cause, which is poverty.”

Fèvre and his fellow researchers have spent years earning the trust of Nairobi residents in the course of a study called “99 Households.” The project examines a variety of homes, from the slums to the wealthy neighborhoods, focusing on the comparative disease risks of those who keep livestock at home and those who do not.

Researchers visit each home once with a medical and veterinary team, taking stool samples from every individual in the household – humans and livestock – and walking around kitchen and livestock areas in special absorbent shoes that pick up microbes from the floor. They also set traps to catch the wildlife – everything from birds and bats to rats, mice, squirrels and mongooses.

Whenever they see risky behaviors, the researchers try to correct them. But in the slums the prohibition on keeping livestock takes a backseat to survival.

“There is a difference between the letter of the law and the practice of it,” Fèvre said. “We stumbled across a guy living in a three-story shack built with scavenged wood and keeping 6,000 chickens.”

In the days after Zika arrived in Miami, Vasquez’s team worked quickly, walking through neighborhoods spraying insecticides from their backpacks. The day after the virus made its first appearance, they searched for anything that could collect water for the mosquitoes to breed in — no bottle cap was too small.

Borr, one of the mothers-to-be, watched the virus change the city she’d lived in since she was 4.

“It felt like a zombie apocalypse was happening, or something. It felt so weird,” she said. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Within a few days, Borr and her husband had decided that she should leave Miami to live with family in Boston. She stayed there for a month and tested negative for the virus.

Still, she missed her husband so much that she returned to Miami in September.

Borr stayed in her home for the rest of the outbreak, armed with hand-held bug zappers and shielded by citronella candles and mosquito netting. She and her husband covered themselves in bug spray and layers of clothing any time they went out. They refused to eat in restaurants where the doors and windows were open.

She wore an impenetrable beekeeper’s suit for her outdoor pregnancy photo, then added a wry, Hollywood-style caption: “Love in the time of Zika.”

Meanwhile, by August, Flores was about five months into her pregnancy. One day, while working at her job in the school cafeteria she received a phone call. It was the lab processing her Zika test. The voice on the other end kept asking questions until Flores posed one of her own.

“Does this mean I have Zika?”

She was told she would need to talk to her doctor.

The answer she finally got was not the one she wanted.

“I started to cry, ‘Oh Lord.’ And then one of the women doctors told me, ‘Take it easy, everything will be OK.’ My reaction was something strong,” she said. “But I asked the doctor, because there was all this talk about Zika, I told her that I had no symptoms, I had felt nothing.”

No fever, no rash, no joint or muscle pain. But the test was positive.

As of mid-June 2017, Flores was one of 351 pregnant women in Florida to show lab evidence of the Zika infection.

It is still early in our understanding of Zika’s link to the birth defect microcephaly: babies born with abnormally small heads due to underdeveloped brains. Doctors could not tell Flores and the other mothers whether their babies would have the birth defects.

They could only monitor the babies’ development every week.

Flores began to pray.

***

In the beginning, Miami’s response to the Zika virus was trial and error.

“We found out that the insecticide that we were using in the spray trucks was no good,” Vasquez said. “This is something that is going on in many places around the world — that mosquitoes have developed resistance to pyrethroid pesticides.”

Resistance occurs when mosquitoes develop protective genes and survive to reproduce. The stronger mosquitoes proliferate, while the others die, allowing the resistance to spread through the population.

In the past, Miami-Dade’s mosquito control team had used pyrethroids, one of two main families of insecticides, to curb black salt marsh mosquitoes. Those mosquitoes had never been exposed to the chemicals and, as a result, had not developed resistance.

Vasquez said the mosquito control team only learned of Aedes aegypti’s resistance when they began spraying and found that it seemed to make little difference. The number of mosquitoes they were trapping remained the same.

After testing various compounds, they switched to naled, a potent insecticide sprayed from airplanes. It doesn’t take much naled to get the job done. An acre can be covered with less than three ounces of the chemical. Still, the droplets in the air caused concern.

Some residents objected to the aerial spraying, worrying about the insecticide’s impact on humans and the environment. But the county continued the practice. Vasquez said the aerial spraying decision was made with the CDC and backed by research demonstrating its success.

“And we saw results,” he said.

Aerial insecticide treatments cut the number of mosquitoes they caught to less than half in a week, significant progress.

Flores’ home was inside one of the Zika zones targeted by the sprayers. Planes flew overhead and she heard about workers spraying inside old houses. Calls from the county would inform her how long to stay inside after the naled was released.

There has been little research on the impact of naled on human health. In June 2017, a study released by the University of Michigan found a link between naled exposure and delayed motor development in infants in China. The research, though far from conclusive, underscored the uneasiness many Miami residents felt.

Borr mostly stayed indoors to avoid the mosquitoes, so airborne naled was not a major concern. She believed public health officials were doing their best, but worried how her unborn child would be affected by the virus, the naled and even the bug spray she was undoubtedly inhaling whenever she did venture outside. The smell of bug spray still makes her stomach churn.

“Our entire way of life changed,” Borr said. “Eventually you sort of develop agoraphobia and you don’t want to go outside any longer because it seems like there’s all these threats and you just get scared in your own head.”

She tried to pass the time knitting and playing Xbox. Still, she imagined bat-sized mosquitoes descending on her and endangering her child. Once, when she heard an insect buzz by her ear, she ran and locked herself inside her office for two hours, hoping it would die.

In Nairobi, not far from where Paul Mugai Ngage raises his family and livestock, stands the next link in the food chain: a small, tin-roofed shack called Quality Butchery. Suspended in the window one morning were the butchered bodies of two cows.

Few slum residents raise enough livestock to feed their families. Most come to a shop like this. Fèvre and his colleagues at the institute have been studying such places in preparation for the next big outbreak.

Following the food chain — from the urban farms and butcheries to the slaughterhouses — allows the researchers to observe how microbes pass between animals and humans. They learn the paths a disease might follow and the places health officials might intervene to control it.

If a virus emerges in a slaughterhouse, for example, it helps to know where the livestock came from and where it was sent next as meat.

While wealthy nations use barcodes to track the route meat travels to the consumer, “food takes different routes here,” Fèvre explained. “In the West, a cow is probably slaughtered 20 days (before sale) and kept in the chiller. Here consumers don’t have fridges.”

Nor do many of the butcheries. Bacteria cling to the feet of the flies that congregate around hanging slabs of pork and beef. Without refrigeration to slow its growth, the bacteria thrive, raising the threat of foodborne illnesses such as E. coli and salmonella. How many Kenyans suffer from those diseases isn’t clear; no national numbers are kept.

However, the Global Food Security Index, which compares the food systems in different countries, ranked Kenya 88 out of 113 countries for food safety and quality. A study of beef in Kenya, published in 2015, said a particularly harmful strain of E. coli “was found at every level from loading to offloading, with the highest occurrence on working surfaces and equipment at the butcheries.”

Fèvre’s team saw an opportunity to improve conditions at Quality Butchery and others like it. In 2014, they picked 60 butcheries, gave fly nets to half of them, then measured the number of flies.

“This is what I would call a success story,” said Akoko, one of the researchers involved in the study. “This butchery, when we first visited, there were lots of flies. We gave them a fly net and talked to them about the flies, and there was a drastic reduction.”

The study also showed a broader change in the marketplace. Butcheries not involved in the study asked for the nets because customers now viewed the flies as unhealthy, and disliked seeing them buzzing around the meat.

Other problems are not so easily solved. Behind the counter at Quality Butchery stands a thick tree stump used as a cutting board. “In Kenya, all of the butcheries have the tree stump,” Akoko said. The tradition has an unfortunate downside; the stump is a magnet for bacteria.

Researchers have tried convincing butcheries to replace the stumps with metal cutting boards that can be cleaned more thoroughly, but they are fighting the economics of a subsistence business. Butchers complain that the metal boards dull their knives much faster. They find a similar disincentive to wash the stumps frequently. The more they wash, the faster the stumps rot.

Even in the larger city market downtown, “there are a lot of gaps in the hygiene,” said Maurice Karani, a veterinary research assistant who works with Fèvre.

There is no ice. There are water shortages. Butcheries sometimes reuse the same water to wash different cuts of meat.

“Where you are standing,” Mohamed Javed said, pointing outside his shop at the floor, “they put chicken in the morning because they don’t have another place.”

Javed, who is 64 and sells beef and mutton to support his wife and four children, complained of corruption, and of competitors who undersell him without revealing how far their meat has traveled to reach the market. Most of his own produce, he said, is raised within 20 miles of his shop.

The 80-year-old business Javed inherited from his father boasts one advantage, however. It is one of the only butcheries in the market to have a freezer.

“It was a big purchase,” Javed said.

***

It is sometimes easier to see the vulnerabilities of other countries than it is to see our own.

In the U.S., few — if any — resort to the use of “flying toilets” or to eating food scavenged from a dump or a slaughterhouse floor. Few sell meat outdoors, where they might require a net to control flies.

The meat we buy is frozen or refrigerated. The butchers who cut it have access to all the ice and clean water they desire.

And yet, in the U.S., we engage in practices that elevate our own risks of disease.

The anti-vaccine movement, triggered almost 20 years ago by a discredited study linking the childhood shots to autism, has led to a resurgence in measles and whooping cough. This spring, Minnesota recorded more measles cases than it had in the 20 previous years combined.

America’s organic food movement has led some to consume raw milk, believing that it strengthens the immune system. According to the CDC, raw milk has been linked to 148 outbreaks of campylobacter, listeria and other illnesses, sickening thousands between 1998 and 2011.

Even our access to high tech medical treatments such as joint and organ transplants comes with its own risk. Of the 1 million people who receive hip and knee replacements each year, about 20,000 contract an infection in the new joint, including the MRSA bacteria that has evolved to be resistant to many antibiotics.

And wealthy and developing nations alike must accept the likelihood that there are deadly pathogens that have yet to reveal themselves.

“Agent X might be the biggest threat ... the emerging zoonotic infection which emerges into the human population that we simply can’t predict,” said Ira Longini, a biostatistician at the University of Florida. “Something like HIV, for example. That’s a big threat. It’s just that we can’t simply know what it is. But it’s clearly there.”

And in today’s interconnected world, “there” could be anywhere.

“It’s gotta give you a certain sense of humility about what else is down the road,” said Dan Strickman, senior program officer at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

“The Zika outbreak — nobody, absolutely nobody expected that.”

Flores’ daughter, Daniella Elizabeth Yac, came into the world suddenly.

On Jan. 27, 2017, Flores went to the school where she worked to request her maternity leave. As she was leaving, she felt an abrupt pain. A co-worker told her to go to the hospital.

When she arrived, Ivan Gonzalez, Flores’ doctor and co-director of the University of Miami’s Zika Response Team, was contacted immediately. As soon as the baby was born, tests would need to be given to assess brain function and eyesight.

News cameras arrived at the hospital as Flores went into labor, an indication of how big a story the tropical disease had become. It was as if the world were standing by, waiting to hear if another baby had been affected by Zika.

That evening, after the baby’s tests were complete, the doctor urged Flores and her husband to relax. At seven pounds, Baby Daniella was healthy and fit.

“I gave thanks to God,” Flores said.

It is too early to say whether Daniella has escaped any damage from Zika. She will be monitored closely for the first five years of her life to verify that her head and eyes are developing normally.

So far, Daniella has escaped the fate of 51 babies born in the U.S. with Zika-related birth defects in 2016.

Flores said she wanted people to know that it is possible to have a healthy baby after being diagnosed with Zika. She is eager to raise Daniella.

“He gave her to me healthy,” Flores said. “And I expect she will continue that way.”

Szapocznik, the Zika expert at the University of Miami, said travel from Latin American countries makes it very likely that if the outbreak there continues, the virus will return to Miami this year. For this reason, one of the key tasks ahead is mobilizing the public against the mosquitoes.

Szapocznik said people have the power to stop the spread of Zika abroad and in the U.S. by following simple steps: emptying sources of standing water, avoiding excessive skin exposure and using insect repellent.

“I think people, through engagement in the process, civic engagement, can really stop this epidemic,” he said.

Most experts say it’s unlikely that the U.S. will see a large-scale outbreak such as the one Brazil experienced. But flare ups are likely, which is why the CDC and others continue to preach mosquito control.

“So that wasn’t a small outbreak because it just fizzled out,” said Strickman at the Gates Foundation. “It was a small outbreak because we did something about it.”

In Nairobi, researchers have tested many of the animals that cross paths with humans every day in the slums.

They have gone to considerable lengths, even venturing inside a cave below the city’s largest slum, Kibera, to sample bats.

“It’s just the most festerous, unpleasant place,” said James Hassell, a graduate fellow from the University of Liverpool working at the Nairobi institute. “You’ve got liquid filtering through the ceiling which is basically human excrement.”

It is important to remember, Hassell added, that while wildlife are viewed as threats in the emergence of diseases, they also play important roles in their ecosystems. Bats take care of insect control; certain birds help with pollination.

Scientists remain curious about the marabou storks that populate the Dandora dump.

Scavenging birds are a particular concern because they cover a greater range than other animals, carrying any pathogens inside them to different neighborhoods. But catching a marabou stork isn’t like capturing a small bat in a net.

“Storks are as tall as a big child,” said Fèvre, Hassell’s colleague. “They have long sharp beaks and need to be caught by basically running up to them and putting a large sack over their heads.”

So far, researchers in Nairobi have been unable to catch one.