Editor's note: text amended May 26, 2017.

February 1, 2016

Kochin, Kerala

Kerala, a lush tropical land, sits at the southwest tip of India, a feather-shaped sliver of earth that extends from the port city of Mangalore in the north to the southern tip of the country. Signs every few kilometers, ostensibly the doing of an over-enthusiastic tourist bureau, announce that you’re in “God’s country”—like a blessing and a threat. One sees little of the raggedy poverty that characterizes other Indian states, ostensibly the legacy of years of communist rule. The sight of hammers and sickles and Che Guevara’s stenciled visage—everywhere—feels charmingly anachronistic. I’m told that Kerala has the highest rates of both literacy and suicide in India. Some speculate that the latter is a product of high aspirations that, when thwarted, turn deadly. A friend from Bombay refers to the state as “tropical Russia.” Everyone reads, everyone drinks, everyone wants to die. (Not unlike their Russian compatriots, Keralans are said to drink like fish.)

Kerala is the epicenter of a decades-long migration to the Gulf, and there are signs of this historic back and forth everywhere. On either side of the NH17, the long and perilous road that runs through the state from North to South, are palatial “Gulf houses,” or ‘Gelf’ in the local dialect. These homes, which conjure elaborate wedding cakes, have been built with money sent back by men who’ve gone off to Qatar, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Oman, and the UAE to try their fortunes. Many have flourishes that appear to have been cribbed from The Arabian Nights. Others approximate pagodas, castles. Very often, these houses of dignity—manzils—are houses without men, each announcing to the world: Here lies the proof of a journey, here lie the fruits of the Gulf Dream. Restaurants in Kerala advertise “Sharjah Shakes,” after the UAE emirate of that name, and women are perfumed by “marhaba,” a scent named after the Arabic word for “welcome.” Dubai-style billboards—which is to say, gargantuan—pop up in lush coconut groves, like objects dropped from the sky.

In the UAE, there are 2.4 million Indians alone, the most recent participants in a migration that began at the end of the 19th century with fishermen and agricultural workers and expanded with the oil booms of the 1970s. Entire villages of men have migrated to cities in the Gulf. It is not uncommon to hear this: “The Keralans built the UAE.”

February 5, 2017

Kanuur, Kerala

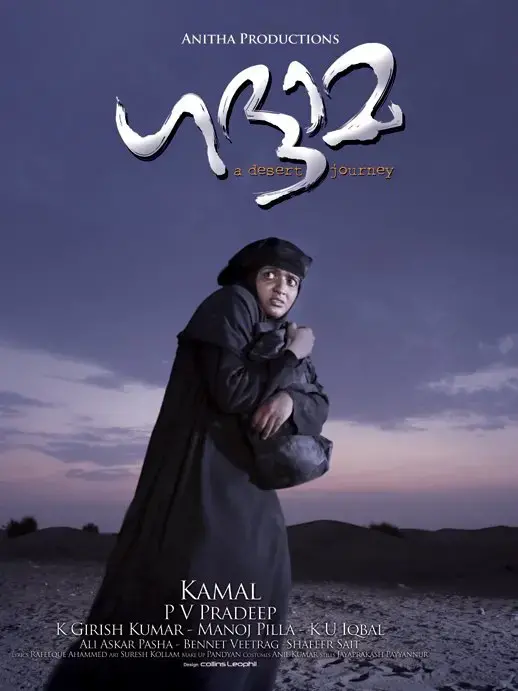

The migration has seeped into popular culture, too. A distinctly Gulfi film industry—Gulfiwood, if you will—has emerged which takes migration as its leitmotif. Not long ago, a film called Gaddama—about a Keralan domestic worker’s travails—was banned in several Gulf countries. There’s even a literature: Goat Boy, in its 10th printing in the local Malayalan tongue and published in English by Penguin India, dramatizes the tale of young Indian man on a Saudi farm. Once weekly, on Kairala TV, a popular program features profiles of people who have gone missing in the Gulf. Littered with horror stories, it makes for grim reality television. A phone number flashes at the bottom of the screen. When I met the show’s host, PT Kunju Muhammed, he relayed garish tales: one fellow kidnapped at the airport and taken to a bleak farm in Oman; another offered one job and stuck with another; yet another roped into sexual servitude; others deported for going on strike (illegal); passports taken away upon arrival. Etc.

Traveling through Kerala, I’m hard-pressed to find a single person who doesn’t have family in the Gulf. Conversations about the migration surprisingly tend not to focus on how difficult life is there, but rather, how it’s beginning to threaten Keralan culture at home. More women veil, it is said, and Arabic words have been creeping into local tongues. No one I’ve met has questioned the migration’s logic as an economic driver. There are legion success stories that have become part of a local mythology, like that of Youssef Ali, who traveled to the Gulf in the 1970s and came back a millionaire. Today, he owns the successful Lulu department store chain, with branches across the UAE. (Confusingly, more than a few people told me that Ali had received the Légion d’Honneur!) “You go to the Gulf to do one thing: make money so you can buy a house and marry,” one Keralan who had worked in construction for decades in Dubai until very recently told me. Yesterday, I met an 82-year-old man who is said to have been one of the first Keralans to migrate to the Gulf. He spoke to me in a lilting British accent, picked up, he said, from British troops stationed in Sharjah: “We had nothing here before the changes. I was a child and hard-pressed to find food to eat. We always hear that when oil was discovered there the face of Dubai changed. But simultaneously, Kerala changed.”

February 12, 2016

Abu Dhabi

The newspapers of the UAE are thick inventories of ribbon-cuttings, launches, openings, and declarations. The day I arrived, the papers were brimming with news of a major cabinet reorganization. There were to be two new ministries, both manned by women, called "Youth" and "Happiness." Words, you could say, take on a magical quality here. Happiness: say it and it will be. A lot of Abu Dhabi seems to work like that, where up until the middle of the last century the land was sparsely populated by Bedouin tribes who subsisted off pearl fishing and occasional pirating.

My destination is Saadiyat Island, where I find myself in the company of pasty European vacationers, golfers, and seasoned conference-goers. And yet most of Saadiyat, fringed by strenuously groomed beaches along azure waters, remains unpopulated, eerily quiet beyond the pong of tennis balls flying back and forth. Saadiyat, in other words, communicates a state of unfinished plenitude. Approaching the island from downtown Abu Dhabi, a billboard announces the future Louvre: "Closer to reality? Closer to inspiration?" The French museum is nearly finished, and appears like a mushroom that has sprouted from the sea, or a single breast in full bloom. Local taxi drivers refer to it as the flying saucer, but the official tag line is "rain of light," in reference to the light that streams through architect Jean Nouvel's eight-layer 12,000-ton lattice dome. On the day I visited the site, I saw blue-suited construction workers scampering along the mosque-like dome, like spider men. Warning signs were festooned on every surface. In June of 2016, a worker fell to his death while putting the final touches on the dome—a revelation that only became public when members of an activist group called Gulf Labor broke the story.

Even before getting here, I was prepared to grapple with the complexities of "the labor problem." In Kerala, I met legion who pointed to the migration as a powerful force in improving lives. I engaged Emiratis about what they made of the conundrum in their midst. Foreigners outnumber Emiratis by approximately 9 to 1; there is no UAE without its foreign-born workforce. And yet, labor abuses persist. Emiratis I speak to often remind me that they live in an inhospitable neighborhood—the Arab world is falling apart all around them. They must balance their opening to the world, they argue, against grim regional realities. This balancing act seems to mark the whole of life in the UAE, as the leadership seems caught between a will to be a part of the world community via their museums and universities and so on, and a conviction that this same opening up—too fast, no less—may undo everything. Inevitably, things like labor reform fall into the category of "too fast." Still, an official from the Ministry of Labor tells me that the UAE's record of labor reform, particularly in comparison to other countries in the neighborhood, is noteworthy. A steady record of change. This is not untrue.

Plainly, pat, sensational media narratives about the Gulf don't help us understand its complexities. This desert is littered with metaphors for devotees of cliché: Ozymandias, castles made of sand, malls, skyscrapers, indoor skiing, slave labor. The architect Rem Koolhaas, an early Gulf booster, has called this strain of criticism "the Disney fatwa." The urbanist Mike Davis, in writing about Dubai in one particularly notorious screed, referred to Dubai as "Speer meets Disney on the shores of Araby." Certainly, it must be exasperating to encounter the same tropes over and over, as though nothing ever changes.

Education Resource

Meet the Journalist: Negar Azimi

Pulitzer Center grantee Negar Azimi sifts through the vexing, perplexing landscape of low-wage...